|

|

Pagan Religious Practices of the Viking Age

|

Little is known about heathen practices in the Viking age. Thanks to Snorri Sturluson's writings and the surviving mythological poems, we know a lot about the myths which form the basis of Norse religious beliefs, but little about day to day practices. The Christian church saw the pagan rites as deviltry, and medieval authors took little interest in them, as compared to the myths. There are some accounts of the pagan rituals by contemporary foreign authors in the medieval literature, both by Christians, and by Muslims, but these sources pose many problems with interpretation. The authors were inimical to the pagan rites. They were foreigners who may not have understood what they saw, or the language that was being spoken. And in some cases, the authors wrote about things they did not witness, using second or third hand accounts. In this section, I've attempted to outline what little is known about the Norse pagan religious practices. Most of the information comes from episodes in the sagas. |

|

The pagan religion did not have the regular organization that was so important to the Christian church. Religion was not a separate institution; it was a part of ordinary life. Rather than special temples and priests, it was maintained by ordinary people in their homes. In the early part of the Viking era, and when away from home, people probably worshiped outdoors. For example, Swedish traders made sacrifices under a giant oak tree on an island in the Black Sea to give thanks for a successful voyage down the river Dnieper.

|

The saga literature provides descriptions of elaborate temples in Iceland. Chapter 4 of Eyrbyggja saga tells of the hof (temple) built by Þórólf Mostrarskegg and dedicated to Þórr, located at the foot of Helgafell, the holy mountain (left). The description is one of the most complete descriptions of a pagan temple extant in the literature. However, it is also highly improbable. |

|

In the saga, the temple is described as a "mighty building". In the middle of the floor was a pedestal on which stood an armring (for the swearing of oaths), a bowl (for sacrificial blood), and idols. To date, no archaeological evidence of such elaborate structures has been found. While large longhouses have been excavated (e.g. in Iceland, at Hólmur near Höfn; at Hofstašir near Mżvatn; and at Hofteigr on Jökulsį į Brś, shown to the right), the evidence that these structures were special-purpose pagan temples is not compelling (although the evidence is compelling that ritual sacrifices were made at Hofstašir). |

|

|

In chapter 15 of Vatnsdęla saga, the settler Ingimundur gamli (the old) chose a site for his home in the beautiful Vatnsdalur valley. He built a great temple one hundred feet long. (Hann reisti hof mikiš hundraš fóta langt.) As he dug the holes for his high-seat pillars, he found his missing amulet of Freyr, as had been prophesized by a Lapp seeress before he left Norway. The temple was on the hill above the farm, to the right in the modern photo of the farm shown to the left. Faint outlines of building ruins are visible, but a recent excavation shows that the structure postdates the Viking age. |

|

Chapter 2 of Kjalnesinga saga says that Žorgrķmur built a temple at Hof, one hundred feet long and sixty feet wide with windows and wall hangings everywhere. In the middle of the hall stood an image of Žórr, with other gods on either side. In front of them was an iron-covered altar, on which a fire always burned. A copper bowl stood on the altar which was used to collect the blood from sacrifices, along with a silver arm-ring on which oaths were sworn. Men who were sacrificed were thrown into a pool that stood outside the door.

|

In the first part of the 20th century, ruins were examined on the site of Sęból in Haukadalur at Dżrafjöršur, in west Iceland. In Gķsla saga Sśrssonar, it says that Žórgrķmur made sacrifices to Freyr there. The Danish archaeologist Aage Roussel reported finding the remains of a temple 6.5m square (21ft) surrounded by walls 14m square (46ft). Today, no ruins are visible on the site (right) because the land was filled and flattened in order to make it suitable for mechanized farming in the middle of the 20th century. |

|

Chapter 49 of Egils saga Skalla-Grķmssonar describes some activities in the main temple at Gaular in Norway. After a sacrifice and feast, men were drinking at night in the temple. Eyvindr and Žorvaldr were paired in a drinking game. Under orders from Queen Gunnhildr, Eyvindr killed Žorvaldr with a sax (short sword). No one else was armed in such a sacred spot; it was unthinkable. Eyvindr had committed murder, so he was declared an outlaw on the spot for defiling the temple.

Adam of Bremen, an 11th century cleric, describes the temple at Uppsala as a splendid building with a roof of shining gold. No traces of such a building have been found near Uppsala.

Norsemen, if they set up any structure at all for worship, probably set up small shrines for their own personal use. Here might be kept a bowl for sacrifices, and an armring for oaths. It seems more likely that worship took place out of doors, beside a mound, a great stone, or a sacred tree. One of the few surviving descriptions of pagan law-code comes from Landnįmabók. The law required that every public temple keep a silver armring, weighing no less than two ounces. The goši (chieftain) was to wear the ring at all assemblies and to redden the ring in the blood of a sacrificial animal. Anyone with business to transact at the assembly was to swear an oath on the ring, calling on Freyr, Njöršur, and hinn almįttki įss (the most powerful god). Does the passage refer to Óðin? Žórr? Tżr? It is not known. The passage concludes saying that each man must pay a temple-tax in the same way "as we now pay tithes to our churches".

A large tree was frequently the source of luck and protection. The world tree, Yggdrasil, plays a central role in Norse mythology. Adam of Bremen writes that there was a great tree standing beside the temple at Uppsala which remained green both summer and winter.

The old Norse word vé appears in placenames throughout the Norse world. It's related to the word vígja, which means to consecrate. A vé was a holy place, where no violence might be done. A person who shed blood in the vé became an outcast. What form a vé took, or how such a place was used is not known.

|

Ólafur Tryggvason was the king of Norway at the end of the 10th century. He forcibly imposed Christianity on Norway. In several sections of Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar, King Ólafur is described destroying pagan temples. The idols were destroyed, the ring taken, and the temple burned down. |

|

|

Few idols have survived. To the left is an idol of the one-eyed Óðin. To the right is an idol of Freyr, clearly a god of fertility with his erect phallus. Chapter 113 of Óláfs saga helga describes one temple idol. King Óláf ruled Norway in the early 11th century. At that time, the pagan religion was no longer tolerated in Norway. In the Fjord district of central Norway, the farmers kept a gold and silver idol of Žórr. The idol was hollow, and every day, the farmers fed the idol with bread and meat as an offering. King Óláf was displeased with the farmers for their pagan practices. One night, he caused their ships to be damaged and their horses to be run off. At dawn, the angry farmers approached the king, carrying the glittering idol. The king said, "Behold the true God comes in the east with great light." The farmers turned to see the sun rising in the east. Meanwhile, one of the king's henchman struck the idol with a club, so that it fell to pieces. Out jumped mice and snakes, so well nourished by the sacrifices that they were as big as cats. The farmers were frightened, and fled to their horses, which could not be found, and to their ships, which were filled with water. The king pointed to the weakness of the god of the idol, and said that the farmers could either convert to Christianity on the spot, or do battle with the king and his troops. The farmers all accepted the Christian faith. |

|

|

Further information about Norse religious practices comes from the writings of Ibn Fadlan. In the year 921, a group of Arabs traveled up the Volga River to visit the King of the Bulghars. Along the way, they encountered Norse merchants, trading on the Volga. To the Slavic residents of the area, these Norse traders were known as the "Rus". Ibn Fadlan, a member of the Arab deputation to the Bulghars, wrote about his encounters with the Rus traders. He wrote that when the traders arrived at the dock of the market place, they disembarked from their boats, carrying "bread, meat, onions, milk, and alcohol [mead]" and went to a tall piece of wood, carved with faces, set in the ground. When the traders reached the idol, they prostrated themselves, and asked the gods for a successful trading mission, saying, "I have brought this offering. I wish you to provide me with a merchant who has many dinars and dirhams and who will buy from me whatever I want [to sell] without haggling over the price I fix." Perhaps the idol at which the Rus merchants left their offerings looked something like the modern idol at Haukadalur in Iceland shown to the left. |

The sagas tell us that worshipers in Iceland also prostrated themselves on the ground in front of idols. Chapter 3 of Kjalnesinga saga tells of Bśi, who thought it was undignified to prostrate himself in that way. Žorsteinn, the son of the temple goši, prosecuted Bśi for false religion (įtrśnašur), and Bśi was sentenced to full outlawry. Bśi ignored the sentence, and later, he came upon Žorsteinn lying face down before Žórr in the temple. Creeping up, Bśi grabbed Žorsteinn, lifted him over his head, and dashed him down onto the stone so hard that his brains spilled out.

In chapter 38 of Haršar saga og Hólmverja, Žorsteinn went to his temple, as was his habit. He went down before the stone in the temple where he sacrificed, and he spoke to the gods.

|

Tiny sheets of gold foil embossed with figures are found in many parts of the Norse world. Typically, these sheets are less than a centimeter square (3/8th inch), and are too light and fragile to have survived much handling. Many have been found in dwellings, under the posts that supported the structure, or under the location of the high-seat. Many depict a man and a woman embracing. One explanation for the foil figures is that they were deposited when the king or chieftain celebrated his wedding, and that the figures represent Freyr and his wife, the giant maiden Gerð. Another explanation is that the foils evoke the landvættir (land spirits) to protect and hallow the building. |

|

The landvættir played an important role in the Norse religion, and their tradition lived on in Iceland for generations after the conversion to Christianity. They were linked with the land itself. Their good favor could bring good fortune in farming, hunting, and fishing, as well as providing protection to children and animals. These spirits were already living in the land when the first settlers arrived in Iceland. Men made sacrifices to the landvættir on hills, at waterfalls, in woods and groves, and at stones.

Landvættir were offended by violence. Certain regions where violent acts had occurred were avoided by men, because of the displeasure of the landvættir. An early Icelandic law required that approaching ships remove their dragon-head prow when coming in to harbor in order to avoid offending the landvættir.

In chapter 57 of Egils saga Skallagrímssonar, Egil twice called upon the landvættir to avenge his harsh treatment at the hands of King Eirik. Eirik declared Egil an outlaw, to be killed by the first person who found him. Egil composed a poem, appealing for justice from the landvættir. Later, after taking revenge against members of the king's family, Egil raised up a nķšstöng, a pole of insult. The pole, topped with a severed horse head and carved with runes, was placed in a prominent spot. After he raised the pole, Egil directed the insult to the landvættir to help him with his cause, saying, "I direct this insult against the guardian spirits of the land, so that every one of them shall go astray, neither to figure nor find their dwelling places until they have driven King Eirik and Queen Gunnhild from this country."

|

Landnámabók states that Ingólfr Arnarson (right) was the first settler in Iceland. When he sighted Iceland, he threw his high-seat pillars (öndvegissślur) overboard and vowed to build his homestead where the pillars were driven ashore. Ingólfr was a deeply religious and circumspect man, and he felt that it was a great test of his luck and fortune to be the first settler in this unoccupied land, where the landvættir populated every hill and mountain. Therefore, he trusted the gods, to whom his high seat pillars were consecrated, to direct him to a farm site that was auspiciously located, and which would not be looked on with disfavor by the landvættir. |

|

|

Ingólfr lost sight of the pillars as they drifted away from the ship. He landed, and after wintering over, he sent his slaves to find the pillars. Not until three years later were the pillars found. Ingólfr moved his farmstead to this new location where the pillars washed ashore, in the present location of Reykjavķk. Interestingly, the slaves had a low opinion of the site chosen by the gods, grumbling about all the good country they passed over in favor of the remote headland where the pillars were found. |

|

The story of Lodmund the Old is told in Landnįmabók (ch. 289). He was another settler in Iceland who threw his high-seat pillars overboard in order to let the gods decide the best place for him to settle. He did not find the pillars when he reached land, and eventually settled in northern Iceland.

Three years later, he learned that his pillars had washed ashore in southern Iceland. Taking immediate action, he loaded all his possessions on board his ship, and sailed away, forbidding anyone to speak his name as he lay down and remained silent. As they departed, a great landslide came down on his house and destroyed it. Lodmund spoke a formal curse, declaring that no ship that sailed from that place in future would ever reach its destination. He then sailed to the location where the pillars washed ashore and built his house there.

Through his actions, Lodmund transferred away from himself that bad luck that fell on him by failing to follow the guidance of the gods who had directed his high-seat pillars. The curse was an attempt to transfer the bad luck to the spot occupied by his original house, while he himself escaped it.

The Icelandic literature repeatedly refers to a seeress (völva), a woman who visited houses, making predictions, particularly about children and their destinies. The stories make clear her importance. A special rite, known as seiðr, was used to obtain hidden knowledge. The seeress, possibly accompanied by an assistant, chanted appropriate poems and spells from the high-seat.

An account of this rite appears in chapter 4 of Eirķks saga rauða. Žorbjörg was a seeress who lived in Greenland. Þorkell, the chief farmer in the district, invited Žorbjörg to his winter feast. At that time, there was severe famine, and Žorkell wished to know when the current hardships might end. Žorbjörg was lavishly received, and a high-seat was made ready for her. She was given a meal, in which the main dish consisted of the hearts of all the animals available there.

|

For the rite, Žorbjörg asked for the assistance of women who knew the witchcraft poems, but none were available at the settlement. Inquiries were made far and wide. Finally Gušrķšur (right, with her son Snorri), who was visiting from Iceland, admitted that she had been taught the poems. But she added, "This is the sort of knowledge and ceremony that I want nothing to do with, for I am a Christian." Žorkell prevailed upon Gušrķšur to assist, and she consented. The women formed a circle around the ritual platform upon which Žorbjörg sat, and Gušrķšur recited the poems. Žorbjörg said that there were many spirits present that had been charmed by the chanting, and that many things had been revealed. She predicted that the famine would end soon, and that Gušrķšur would return to Iceland to start a great and eminent family. Both predictions came to pass. |

|

Feasts and sacrifices were an important part of Norse religious rites. While feasts and sacrifices might be made on special occasions, there also were regular feasts in which all the community took part. One occurred at the beginning of winter, when sacrifices were made for plenty during the approaching winter season. Another occurred at mid-winter for the growth of crops that would be planted in the spring. And a third took place in the spring, for victory and success on raids and other expeditions to come in the summer.

These festivals were a time for extended feasting by the whole community. Sacrificial animals were killed and eaten, and ale was drunk in honor of the gods, and in honor of departed kinsmen and ancestors. An essential element seems to have been that the entire community eat and drink together, although other community activities, such as games and contests, were likely to have been a part of the festivities.

Chapter 107 of Óláfs saga helga briefly describes the feasting ritual. In the beginning of the 11th century, King Óláf of Norway learned that the farmers in the Trondheim district held great feasts at the beginning of the winter. Toasts were made to the Æsir. Cattle and horses were slaughtered, and their blood used to redden the idols. These sacrifices were performed to improve the harvests.

Another episode in chapter 91 of the saga highlights the importance of these rituals. Sigvatr, one of the poets of King Óláf of Norway, was sent on a diplomatic mission to Sweden. At that time, most of Norway had converted to Christianity, but most of Sweden remained pagan. One night during his journey, Sigvatr and his traveling companions sought shelter at a farm house, but as Christians, they were turned away because a sacrifice to the elves (álfablót) was being made. The woman at the door said, "I dread Óðin's wrath, we are pagan here." This withholding of hospitality to travelers was unthinkable in the Norse world, so this act underlines the importance of the ceremony taking place within the house.

|

|

Recent archaeological evidence has added to our knowledge of ritualistic practices in the Viking age. The house at Hofstašir in north Iceland was a large, imposing house, and it seems highly likely that ritual activities took place within the house on a regular basis. Skeletal remains of animals found on the site suggest that cattle in their prime were slaughtered by striking the animal between the eyes while simultaneously beheading it with a two-handed axe, creating an impressive fountain of blood in a dramatic display of weapon-handling prowess. The skulls were then displayed outdoors for months, or perhaps years (left). |

This sort of sacrifice was called a blót. The offering was meant to strengthen the gods, who would thus look more favorably on the people making the offering. Animals were sacrificed, and as part of the ritual, the participants ate the meat and drank the ale, both of which were blessed by the chieftain. The participants drank to the gods: to the Æsir for victory, and to the Vanir for fertility and peace. One of the more complete descriptions occurs in in chapter 14 of Hákonar saga góða. All kinds of animals, including horses, were slaughtered. Their blood was sprinkled on the walls of the temple, as well as on the participants in the feast. The meat was boiled in cauldrons in the temple and eaten at the feast. Drinks were passed over the fire, "signed" by the chieftain giving the feast, and toasts were made to Óðin, Njöršur, and Freyr.

At least one modern source rejects this interpretation of the blood-sprinkling ceremony from Hákonar saga góða, using verse 1 in Hymiskviša as an additional source. That verse suggests that sacrificial blood was sprinkled and used for prophesies, by reading the patterns of the stains where the blood fell.

A spring (right) near the site of the temple at Gošanes in east Iceland is called Blótkelda (spring of sacrifices). The red color of the iron-rich rocks and water was thought to be due to the blood from the sacrifices there. The sacrifices are what separated pagans from Christians, according to the medieval Icelandic lawbook Grágás. "Christians attend churches; heathens sacrifice at temples." |

|

When Iceland accepted Christianity, the Alþing made the law that all men should be baptized and become Christian. However, the law also permitted many of the pagan practices to continue in public, such as the eating of horse meat, but not sacrifices. Sacrifices to the gods were permitted only in private.

The sagas suggest that after the law was passed, baptized Christians continued to observe some of the heathen ways. Chapter 54 of Eyrbyggja saga tells that Žóroddr and his men were lost at sea and presumably drowned. At their funeral feast, Žóroddr and the others walked in to the room, all soaking wet. The saga author comments that if drowned men attended their own funeral feast, it was a sign that Rįn, the goddess of the sea, had accepted the drowned men. Thus, the guests at the feast thought the appearance of the men was a good omen. The author adds that at the time of the saga, many baptized Christians still held heathen beliefs.

|

The sprinkling of the blood of the sacrifice appears to have been an important part of the sacrificial rite. The blood of the sacrifice was called hlaut, and the sagas speak of a bowl used for collecting the blood, which was kept in the shrine. (The historic stone bowl shown to the left has been interpreted as a sacrificial bowl. I am skeptical, but it's as good a guess as any as to what the bowl might have looked like.) |

|

The bowl shown to the right was found in Gošdalur in west Iceland (shown to the left as it appears today) and is thought to be an ancient sacrificial bowl. Indeed, traces of blood have been positively identified in the interior of the bowl. Blood from these bowls was sprinkled on the walls and on the participants to infuse the space with power, and as a protective measure to avert ill-luck. When blood was sprinkled and toasts were drunk, men were symbolically joined with their gods and their dead ancestors. |

|

|

The sacrifices were intimately tied to legal proceedings, as well. Each goši (the chieftain who was both the political and religious leader in a region) was required to wear to all legal assemblies a silver arm ring reddened in the blood of an animal he himself sacrificed. Two typical arm rings from the period are shown to the right. |

|

|

Another description of a feast appears in chapter 17 Hákonar saga góða. Early in the 10th century, King Hákon of Norway was a Christian at a time when few of his subjects were. He was in Trondheim at the time of a feast at the beginning of winter. Normally, when King Hákon was present at a place where sacrifice was made, he would eat apart, with only a few of his men. But the farmers of Trondheim expressed their disappointment that the king was not sitting in the high-seat at a time of such good cheer. Earl Sigurð, one of the king's men, convinced Hákon to occupy the seat, in order to placate the farmers. When the ale was served, Sigurð took the horn, dedicated it to Óðin, and drank to the king. The king took the horn, and made the sign of the cross over it. The farmers objected. Sigurð calmed their unease by explaining that the king dedicated the drink to Žórr, and that he had made the sign of the hammer over the horn, not that of the cross. |

The next day, when the sacrificial horse meat was served, the king refused to eat any. The farmers asked him to drink some of the broth. The king refused. They asked him to eat the drippings from the meat. The king refused. Finally, the farmers asked the king to gape with his mouth over the handle of a cauldron on which the smoke of the horse meat had settled. The king went to the cauldron, covered the handle with a cloth, and then gaped. Neither party was satisfied.

The following winter, the eight chieftains in the Trondheim district made plans to ensure the king's participation in the upcoming sacrifice. They burned down three Christian churches in the region, killing the priests. King Hákon and Earl Sigurð arrived with their supporters, but the farmers were present in large numbers. They thronged upon the king and his men, and they demanded that the king and his party sacrifice with them. If the king failed to join the feast voluntarily, the farmers were prepared to force him to feast. The king ate a few bits of horse liver, then left immediately, saying that he would return at another time with greater forces and return the hospitality shown him by the people of Trondheim.

To the farmers, the king's participation was important, because the well-being of the land depended on his taking part in the feast.

Besides the regular annual feasts, other gatherings took place at longer intervals. Some of these may have been regular, but some may have been for special occasions, such as times of danger, times of famine, or thanksgiving after a victory.

Adam of Bremen was an 11th century cleric and was the Archbishop of Bremen's expert in missionary affairs. Adam wrote about affairs in Scandinavia during this time. His book, Gesta, is a valuable, although flawed, resource. It represents some of the earliest written literature about Scandinavia. But most of it is based on second hand and third hand information.

Especially valuable is his description of the pagan practices which still took place at that time in Sweden. Adam wrote that every nine years, sacrifices of animals and men were made at the temple at Uppsala. Afterwards, the bodies of the victims were hung on trees by the temple. The festival lasted for nine days, with one human victim offered daily, along with each species of animal or bird. Adam did not witness these events, but wrote about them based on second hand information: He wrote:

|

It is the custom moreover every nine years for a common festival of all the provinces of Sweden to be held at Uppsala. Kings and commoners one and all send their gifts to Uppsala, and what is more cruel than any punishment, even those who have accepted Christianity have to buy immunity from these ceremonies. The sacrifice is as follows: of every living creature they offer nine head, and with the blood of those it is the custom to placate the gods, but the bodies are hanged in a grove which is near the temple; so holy is that grove to the heathens that each tree in it is presumed to be divine by reason of the victim's death and putrefaction. There also are dogs and horses hang along with men. One of the Christians told me that he had seen seventy-two bodies of various kinds hanging there, but the incantations which are usually sung at this kind of sacrifice are various and disgraceful, and so we had better say nothing about them. |

|

The sacrifice was made at the beginning of summer, the traditional time of offerings to Óðin, in return for victory in the coming season.

|

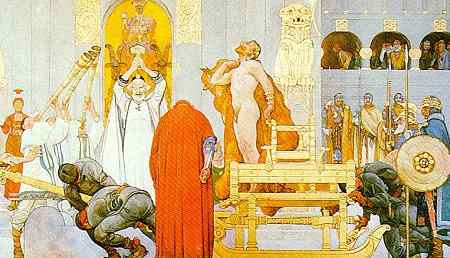

In chapter 15 of Ynglinga saga, Snorri describes a situation in which a king was sacrificed during a time of extreme troubles. The events in this saga occurred early in Norse pre-history, perhaps in the 7th century. During a time of famine in Sweden, huge sacrifices were made at Uppsala in the fall. The first year, they sacrificed oxen. The second, they sacrificed humans. The third year, they decided that the famine was due to their king, Dómaldi, and that they should sacrifice him and redden the altars with his blood. This they did. The image to the left is a detail from an early 20th century painting by Carl Larsson, showing this sacrifice. |

In most cases, it appears that the humans chosen for sacrifice were wrongdoers: thieves, and slaves, primarily. In chapter 12 of Kristni Saga, it is stated that "heathens sacrifice their worst men." Chapter 67 of Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar describes King Óláf Tryggvason's attempts to force Christianity on Norway at the end of the 10th century. The king threatened to introduce new sacrifices if people refused to give up the old religion, and that victims would not be slaves or criminals, as was customary. The king said, "I shall not choose þrælls (slaves) or evildoers, but those selected as a gift for the gods will have to be the most distinguished men," naming ten prominent men in the group of farmers facing the king.

|

One of the few references to human sacrifice in the Icelandic literature occurs in chapter 10 of Eyrbyggja Saga. During the 10th century, a holy site where men met in Assembly was defiled by a skirmish between two families in which blood was spilled. As a result, the site of the regional assembly was moved. The narrator of the saga (writing in the 13th century) describes the new site, saying, "The circle where the court used to sentence people to be sacrificed can still be seen, with Þór's Stone inside it on which the victims' backs were broken, and you can still see the blood on the stone." The photo shows Žórssteinn as it appears today, and you can still see the blood on the stone. The top of the stone has a reddish color similar to dried blood.

|

|

Perhaps the most notable example of human sacrifice in the Icelandic literary records occurred on the day the Alžing was considering the adoption of Christianity in the year 1000. The heathens present at Žingvellir decided to sacrifice two men from each of the four quarters, according to chapter 12 of Kristni saga. The heathens called on the gods to prevent the spread of Christianity through the land.

When an animal sacrifice was made, the hide, with head, horns and hoof attached, was set up outside the house as a record of the sacrifice. At the annual assembly of the Icelandic parliament (Þing), a bull was sacrificed, and the sacred ring on which oaths were sworn was washed in the blood of the animal. However, horses were more commonly sacrificed as a symbol of power and virility. There are many accounts, as well as archaeological evidence, of horses being killed as part of funerary rites.

To the Norse, the gods were friends, or even distant family, to whom one turned both in good times and bad. To foster the two-way trust that was needed for such a relationship, Norsemen frequented sacred places, ate and drank in the gods' honor, and offered gifts and sacrifices in return for luck and protection. They made offerings to the Æsir for victory, and to the Vanir for good harvests and fertility. In return, they expected that their prayers would be answered.

Despite these regular sacrifices, there appears to have been no regular priesthood, and no single-purpose temples. The leading men in each community performed the ceremonies in their homes. The rituals held the community together, giving men fixed points in the year to which they could look forward, and enabling them to meet and unite in giving thanks.

The Roman and Greek religions were populated with deities that were organized into an elaborate scheme. Each deity was responsible for one particular aspect of life.

The Norse religion could not be more different. The responsibilities of the deities were not so clearly defined. Gods and goddesses had overlapping dominions. No one god had sole dominion over the sky, or the earth, or the underworld. While the character of each god is recognizable, the choice of one as a divine protector depended on the man doing the choosing. A king or warrior turned to Óðin. The common man, the traveler, or a man holding land and responsibility turned to Þór. Those who reared animals, cultivated the land, and raised families turned to Freyr, or another one of the Vanir.

Unlike Christianity, there was little connection between the Norse pagan religion and morality. A Norseman lost the favor of the gods not by breaking some universal commandment, but by offending the gods themselves in some way. The fundamental criteria by which conduct was evaluated were honor and shame. The most desirable thing a man could attain was the esteem of the community during his life, and fame and good repute after his death. The chance of attaining fame and everlasting renown became the fundamental ideal for human life, and was worth any risk.

|

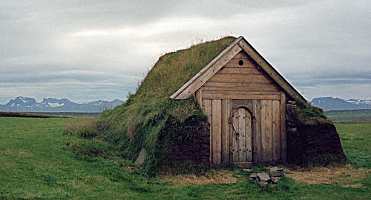

Not all the Norse people in the Viking age were pagan. Some accepted Christianity, either from contacts with Christians in trading centers or other lands, or from conversions that were taking place in some of the Viking lands in the later part of the 10th century. Some settlers in Iceland brought the new religion with them and built churches at their new homes. The church shown in the photos is a reconstruction of the church at Geirsstašir built in the year 980, twenty years before Iceland converted to Christianity. The church ruins were recently excavated and studied. |

|

|

Landnįmabók says that although some Christian settlers arrived in Iceland, they didn't keep up their faith. Their children built temples and made sacrifices according to the pagan ways, and that for the 120 years before the conversion, Iceland was completely pagan. Chapter 97 tells of Aušr, who claimed the entire Dalir district when she arrived in Iceland. A devout Christian, she erected crosses at Krosshólur (left) and said her prayers there. Later, her descendants sacrificed and built a pagan temple on the site. It would have been challenging for Christians in Iceland to engage in the community before the conversion in the year 1000. Since law and religion were tightly interwoven in pagan Iceland, it would have been difficult for a Christian to participate in the legal system. Oaths were sworn on a blood-reddened ring, something a Christian man would be unwilling to do. |

Additionally, it's unlikely there were priests to sing mass or to conduct the other functions of the church. Yet, some Icelanders kept their Christian faith between the settlement and the conversion. Landnįmabók (S 320) tells of Ketill hinn fķflski (the foolish), a Christian who settled at Kirkjubęr. No heathens were allowed to live there, and the family remained Christian throughout the period before the conversion.

The conversion of Iceland to Christianity in the year 1000 is a remarkable story, told in more detail in a separate article.

|

The available evidence concerning the Norse pagan religion is confused. It's an incomplete and distorted picture of a fluid and changing body of religious beliefs and practices. We can recognize the characteristics of the Norse gods and goddesses who rule the supernatural world and shape the destinies of men. Men sought the protection of these deities, through sacrifice, feasting, and by endeavoring to ascertain their will and retain their favor. By supporting them, men maintained the natural order, ensured the survival of their family, and enjoyed the regular progression of the seasons and renewal of the earth on which their lives depended. Men were aware of the threats that menaced them, but they were also aware that the order of the world and the prosperity of their community would not last forever. The rites which supported the gods helped to maintain the established order and kept out the chaos that continually threatened and which eventually would dominate. Worship included beings linked to the natural world: rocks, mounds, springs, lakes, caverns, and hills. Reliance on these beings was of paramount importance. Worship involved sacrifice and the giving of gifts, and was coupled with the desire to learn the future in order to adequately prepare for what was to come. |

|

An important aspect of the religious beliefs is the belief in luck. Luck was essential if one was to survive. A lucky man fit into the natural world and possessed the protection of the powers that governed it. Skills and other outstanding gifts were insufficient to protect a man if he were unlucky.

|

There was no obligation to accept a particular god. If one's luck failed, one could desert one god in favor of another. No doubt that some Norse pagans turned to Christ because He gave hope for better luck than the pagan god they previously worshipped. The comfortable overlap between pagan and Christian beliefs is exemplified by the description in Landnámabók of Helgi inn magri Eyvindarson (Helgi the Lean, shown in a modern statue to the left), one of Iceland's first settlers. He prayed to Christ when at home (where things were safe) but to Žórr when at sea (where things were dangerous). Helgi called on Žórr to show him where to settle in Iceland, but named his new home Kristnes (Christ's headland). |

It is not suggested that Norsemen led devout lives, filled with religious observances. Egil Skallagrímsson's poem Sonatorrek, composed on the death of two of his sons (shown in a modern sculpture to the right), illuminates the relation between the pagan Norseman and the gods better than perhaps any other surviving literature. As a poet and a warrior, Egil appreciated Óðin's gifts above everything else. |

|

Norsemen pursued their daily activities, using what means they had at their disposal to make their way through life. But it was taken for granted that order was maintained and chaos held at bay by the intervention of the gods, and that to be on their side ensured continued luck and survival.

|

A video presentation on Religion, Myth, and Cult in the Viking Age by Dr. William R. Short, manager of Hurstwic, LLC. The lecture was part of the Hurstwic Heathen study group series of presentations and discussions. |

|

|

©1999-2026 William R. Short |

|

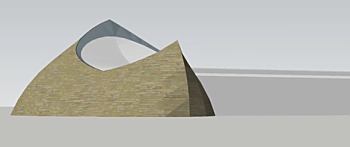

In Grindavķk, on Reykjanes in Iceland, a modern interpretation of a pagan temple (left) has been erected. While it's not clear that the designers and builders of this modern temple had any special insight into how pagan temples were built during the Norse era, it is fun to see all the motifs from the various temple descriptions brought together into one structure. Late in 2003, plans were announced to build a new temple in Akranes, Iceland. I am not aware of any construction ever having been started. |

|

In 2008, I learned that Įsatrśarfélagiš (Icelandic Heathen Association) had begun planning for a new hof (heathen temple). Land had been set aside at Öskjuhlķš in Reykjavķk for the structure.

News reports at the beginning of 2015 suggested that construction will begin later

in the year. The plans call for a partially buried dome encompassing 350

sq m (3800 sq ft) with room for 250 people.

During an open house on the site in spring 2023, I saw the offices and meeting room on the site, as well as the space that will eventually be partially domed over to create the ceremonial space (right). |

|