|

|

Land Travel in the Viking Age

|

Much of the text presented on this page is out-of-date. Until we find time to make the needed updates to this page, we strongly encourage readers to look at this topic as it is presented in our new book, Men of Terror, available now from your favorite book seller. |

People traveled widely during the Viking age for a variety of reasons: for trade; for battle; for socializing; for feasts; for games. Because of the topography of the Norse lands, a water route was usually preferred. But when that wasn't possible, people traveled overland.

The difficulties of land travel varied from region to region in the Norse lands. For example, Denmark's terrain has few of the challenges of the rugged indented coasts of Norway or Iceland (right). |

|

Little archaeological evidence survives that provides any details about land travel. The best we can say is that when people traveled overland, if they didn't walk on their own two feet, they used horses, carts, wagons, sledges, skis, skates, or pack-horses.

|

Outside of towns, roads, where they existed at all, were simple paths rutted by cartwheels. In covering the route from one place to another, parallel "roads" existed, using different routes for different purposes (driving animals, compared to carrying cargo, for instance). Carts might take one path, while a rider on horseback followed a different one. If one route became impassible, a new one quickly sprang up alongside it. The old path alongside Lagarfljót in east Iceland is shown to the left. The rocks show the scars of countless feet, hooves, and cart wheels. Roads tended to follow natural routes, avoiding marshy places and wetlands. If wet areas had to be crossed, they were covered with wooden planks or brushwood. |

In a few places, more sophisticated roads were built, such as the road at Risby in Denmark, shown in a sketch to the right. It is lined with stone curbs and paved with flat stones on a gravel bed. Some river fords were paved with stones, such as the ford at the Nyköping river at Släbro in Sweden. Rune stones at each end commemorate the person who created the ford and also show the route when snow-covered. |

|

Wooden bridges were built using wooden piles driven down into whatever solid ground existed below the water, braced with wood and spanned with wooden planks. While the construction details remain unclear, some of the bridges must certainly have been massive undertakings. The bridge at Ravning Enge in Denmark was 700m long (about a half mile) and was supported on more than 1000 piles driven into the ground.

The justification for the bridge remains a mystery. In the wet ground, the wood probably lasted no more than 30 years, but there is no evidence that the bridge was ever repaired after it was constructed.

|

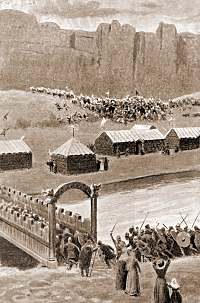

In the Viking age, a bridge stood at Žingvellir in Iceland, spanning the Öxarį river. The bridge is mentioned in a number of sagas, as the site of a battle (Brennu-Njįls saga, right) and as a site for bathing (Hrafnkels saga). The most probably location of the bridge is over the narrow part of the river that is adjacent to the modern church seen in the left photograph, upstream from the modern bridge that is closer to the lake. |

|

|

Little information exists about the kind of carts or wagons used in the Viking age because few have survived. The most famous is the Oseburg wagon (left), found in a very rich burial. However, the wagon must surely have been built for a very special purpose, something other than transport; it is richly decorated to a very high standard and is constructed such that it can not turn. |

|

Some of the best evidence about wagons comes from tapestries. The Oseberg tapestry shows wagons being drawn by horses (typically one, but sometimes two) using breast-harnesses or collars. This kind of harness would have allowed enough tractive force to pull a load of about 500kg (1100lb). |

|

|

In winter, sledges were the preferred means for transporting cargo overland. In some ways, overland transportation was actually easier in winter. Frozen lakes, rivers, and marshes made some of the routes very much easier than in summer, and a sledge could carry heavier loads than a cart. People waited until winter to transport heavy items such as timber and stones. The simple sledge from the Oseberg burial consists of a frame and bed attached to two up-turned runners. A box-like body could be fitted to the sledge in order to carry more cargo. The reproduction sledge shown to the right is based on the Gokstad find. |

|

|

Horses in the Viking age probably resembled modern Icelandic horses. They are small (14.5 hands, about 150cm), but very sturdy and strong. An Icelandic horse breeder told me that he expects a typical speed for horse and rider on a long trip to be 6 - 8 km/h (about 4mph). Much greater speed is possible for short distances. In chapter 157 of Ķslendinga saga, it is said that Sturla and Órękja rode from Flugumżr to Grenjašarstašur in two days, a very routine ride. The distance of their route would have been about 130km. |

|

| Since rich or powerful men were frequently buried with their horse, a great deal of horse equipment survives as grave goods. The skeletal remains of a horse shown to the right are part of a burial of a Viking-age male. While the equine skeletal remains survived reasonable well (jaw and teeth to the left, along with four limbs and part of the backbone), the human bones did not. Only a portion of the skull and a few other human bones survived. The man's cloak pin (upper right) and the horse's bit (left) also were found in the grave. |

|

|

Snaffle bits (left) were the most common type of bit. Stirrups (right) typically had tall hoops with heavy square loops for the leather strap. The spur shown is made of iron with a fine inlay of decorative silver and copper wires, and it has an animal head design on the prick. The grave finds suggest that bridles were very showy with decorative mounts. |

|

|

|

Horseshoes were not known to have been used in the northern lands until after the Viking age, although in winter, horses were shod with iron spikes (left and right) in order to draw sledges. |

|

|

Saddles are rarely found, but were probably made from wood and leather. They used two saddle panels resting on the ribs on each side of the horse's spine, with a high pommel (in front of the seat) and cantle (behind the seat). Mounting rings allowed loads to be carried as well as a rider. The wooden portions of the saddle from the Oseberg ship burial are shown to the left. |

|

The author of Fljótsdęla saga comments that in saga days, most people rode in saddles that had high pommels. The image to the right shows a horse from the Bayeux tapestry with such a saddle. It is believed that the saddle was placed far forward on the horse's back, and that long stirrup straps allowed the rider to sit with his feet stretched out in front of him. That seating position is illustrated in the Bayeux tapestry, and in the wood carving of a horse and rider on the 13th century church door at Valžjófsstašur in east Iceland (left). |

|

|

Pack saddles were also used. The photo shows a 20th century pack saddle from Iceland which differs only slightly from medieval pack saddles. Some special-purpose pack saddles are described in the sagas. In chapter 8 of Vopnfiršinga saga, Geitir devised a plan to recover the bodies of dead kinsmen in empty charcoal bins (kollaupur) on horses' backs. Some pack saddles, called hrip, had quick releases to dump their loads and were used to carry peat and other heavy loads. In chapter 20 of Ljósvetninga saga, men being pursued were placed in pack baskets on horses, covered with grass, and then calves was laid on top of them in the baskets. The pursuers suspected nothing as the horses carrying the hidden men were led past them. Once to safety, the release was pulled, and the men dropped out the bottom. |

Skis and skates were certainly used for sport, but also had practical uses for travel in winter in the Norse lands. On snow covered ground or ice, travel on ski or skate would have been much easier than struggling through the snow on foot or on horseback. The 16th century illustration to the right shows both skis and skates in use in Norway. Literary evidence suggests skis were widely used in Norway, but rarely in Iceland. One of the few examples in the sagas where skis were used in Iceland is in chapter 6 of Valla-Ljóts saga. Sigmundur was staying as a guest at the farm of Upsir in north Iceland, when one of his enemies arrived, who sought shelter from bad winter weather. The farmer invited all to partake of his hospitality and warned against any attack during the night. Sigmundur left the house and used skis to round up supporters for a revenge attack. |

|

Several different styles of skis have been found. Most skis are made from pine, in part because the pine resin helps the glide of the ski. Some skis are relatively short (165cm), with a polished gliding surface and a raised plate for the foot. Horizontal holes carried the straps that attached the skis to the foot. The underside was often grooved for stability and additional glide. Longer skis were also used. The sketch to the left shows one of a pair of skis from 12th century Norway that are about 210cm long. Unmatched skis were used as well, especially for hunting, with one long gliding ski on the left foot and a short, fur-covered kicking ski on the right for propulsion. A single ski stick (skķša-geisli) was used for balance. |

|

Ice skates were made of bones, usually from the metatarsal bones of horses or cattle (left). Leather straps or lace threaded through horizontal holes in the bones were used to tie the skates to the feet (right). An iron-tipped pole was used for propulsion. Because the skates have no edge, it is not possible to turn or stop as with modern ice skates. However, good speeds are easily obtainable. An article about our attempts to make and use reproduction bone ice skates is available here. |

|

It appears that men used camouflage to hide their movements while traveling overland. Ljósvetninga saga (ch.10) says that Žorkell traveled to a žing meeting to press a case forcefully with a large number of supporters. He did not want to tip his hand by travelling with a large party, so Žorkell and a small number of men rode to the assembly via the normal route. Meanwhile, a much larger party took a different route, where the color of their tents blended with the woods. The two parties met, and no one at the žing was aware of the large number of men waiting to support Žorkell in his case.

The difficulty of land travel in the Viking age should not be underestimated. Many natural features presented insurmountable obstacles to travel.

Some rivers could not be easily crossed. Powerful glacial rivers such as Jökulsį į Brś in east Iceland have no natural crossings or fords for many miles in either direction. People built bridges, or took advantage of natural stone bridges where they existed. |

|

|

Ferries were used to cross rivers and fjords. One of the old stone boat sheds for the ferry across the Tungnaį river in south Iceland is shown to the left. |

In lands with many fjords, such as Iceland and Norway, it often was much faster and more convenient to take a ferry, rather than have to ride all the way around the fjord to get to the other side. Gķsla saga says that when Vésteinn wanted to cross Dżrafjöršur to visit Gķsli, he took a ferry that left from this stream and took him to Žingeyri. (The modern town of Žingeyri is just visible in the photo on the opposite shore.) Véstein's alternative was to ride more than 35km around the fjord, so the 3km row across the fjord was an attractive alternative. |

|

|

Glaciers posed many problems. Travel over the glacier was treacherous and not routinely attempted. Powerful glacial rivers below the glacier could be unpredictable in their course, depth, and flow. Instead, travelers journeyed behind the glacier, across the desolate interior (left) to make their way around the glacier. |

In order to find their way in these desolate areas, travelers built rock cairns: piles of rocks to mark the route. The one shown to the right is along a traditional route to Žingvellir. |

|

|

In both settled and unsettled regions, people used prominent, easily-recognized landmarks as navigational aids. The three peaks of Žrķhryningur (left) can be seen all over the Rangį valley in Iceland, as well as in the uninhabited regions behind them, providing an unmistakable landmark for travelers over a wide area. |

A featureless highland heath (right) was difficult enough to navigate in fine weather, but treacherous in fog or blowing snow or other conditions of reduced visibility. Difficult travel conditions also existed on steep slopes along the shores of fjords, where uncertain footing resulted in people sliding off the path to their death. |

|

|

Other types of terrain simply could not be crossed. Rough lava fields chewed up feet and shoes and broke ankles and legs. The lava field Berserkjahraun in Iceland (left) was avoided, resulting in a long detour around the lava, until Styr tricked a pair of berserks into building a path, as described in chapter 28 of Eyrbyggja saga. The path is still visible today. |

|

An important aspect of land travel in Norse lands was the giving of hospitality. A traveler expected the door of even the most modest farm to be opened to him for warmth, food and drink, and shelter for the night. In a winter storm, Böšvarr and his party lost their way as night fell, as is told in chapter 6 of Valla-Ljóts saga. They stumbled upon a farm and asked for hospitality, which was granted. Also staying there was Žorgrķmur, who had a score to settle with Böšvarr. The farmer said he intended to treat his guests well, and he expected his guests to behave well amongst themselves. Žorgrķmur betrayed the farmer's trust, and slipped away in the night to set up an ambush. Chapter 51 of Eyrbyggja saga says that on a stormy night, travelers were carrying the body of Žorgunna overland to where she wished to be buried. They stopped at a farm and asked for hospitality, but the farmer refused. In the night, loud noises were heard in the pantry. It turned out to be Žorgunna's ghost, preparing a meal for the travelers. The startled farmer immediately offered hospitality to the travelers that had been withheld earlier, kindling fires, taking their wet clothes and offering them dry ones, serving up the meal prepared by the ghost, and finding comfortable places for the guests to sleep.

On one hand, the old poems, such as Hįvamįl teach that hospitality should be offered to travelers. But on the other hand, stories from the sagas suggest that hospitality was not always forthcoming. Perhaps the most egregious example is from chapters 71 and 72 of Egils saga. Egill repaid poor hospitality by gouging out his host's eye and cutting off his beard before departing in the morning. |

|

|

©1999-2025 William R. Short |