|

|

Other Viking Artifacts in North America

There

are a small group of Norse artifacts found in North America that are widely

regarded as genuine. These include the artifacts found at L'Anse aux Meadows

(left) and the 11th century Norwegian coin found in Maine in 1957 (right).

There

are a small group of Norse artifacts found in North America that are widely

regarded as genuine. These include the artifacts found at L'Anse aux Meadows

(left) and the 11th century Norwegian coin found in Maine in 1957 (right).

In addition, there are a large number of artifacts not widely accepted as genuine. These range from the carefully studied extant artifacts (such as the Kensington rune stone) to the legendary (such as the Cape Cod ossuary) of which nothing tangible remains.

Since many of the artifacts were found in Hurstwic's home

territory of New England, we present here a summary of some of the more interesting ones,

and some of the more bizarre speculation, with

the disclaimer that none of these is generally recognized as genuine.

Leifur Eiríksson visits Boston

|

The Boston area is graced with not just one, but three public monuments commemorating Leif's visit to the area. One of these monuments marks the precise location of Leif's house in Cambridge, near the banks of the Charles River. How do we know the location of Leif's travels so precisely? The simple answer is that we do not. However, at the end of the 19th century, Eben Norton Horsford, a professor of chemistry at Harvard, felt that he had proof of Norse settlements in several towns along the Charles. Horsford wrote extensively about his findings and had a hand in the creation of the various monuments. During his life, Prof. Horsford made a fortune through the commercialization of his chemical processes, notably, his process for making baking powder (left). Towards the end of his career, Horsford met Ole Bull, a Norwegian violinist and nationalist who made regular visits to America. Bull catalyzed Horsford's interest in the Vínland settlements. Together, they worked to raise funds to fulfill Bull's dream: a statue of Leif in America. The dream was not realized until after Bull's death, but Horsford saw the project through to its completion. A statue was commissioned and placed on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston (right). |

|

|

Subsequently, Horsford decided to search for the location of the Vínland settlement. He used the research methods that had served him so well in his chemical researches. Using the Vínland sagas as his source, he hypothesized the location of Leif's settlement in Vínland. To test his hypothesis, Horsford started digging at the spot. This was an easy dig, since it was only a few blocks from his home in Cambridge. Horsford found a mishmash of stones (right, taken from the plate opposite page 97 in ref [2]) and proclaimed the site to be that of Leif's home. |

|

|

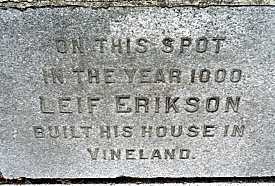

Horsford placed the stone tablet (left) which, to this day, marks the location of Leif's house. (The tablet is located at the junction of Memorial Drive and Gerry's Landing Road in Cambridge, between the traffic light at the intersection and the Mt. Auburn Hospital.) |

|

Horsford continued his research, finding evidence of Norse era dams, canals, piers, and settlements in Watertown, and a Norse era fortification in Waltham. Horsford oversaw the re-creation of the fortification: a stone tower in the Norumbega region of the Charles River (right). The tower is located on Norumbega Road, near the intersection with River Road. Horsford hypothesized an extensive series of North American settlements, with a population of nearly 10,000 people, which thrived for three centuries. He proposed that the economic basis for the settlements was mazer wood, the round burls (left) that grow on the sides of trees. These burls are valuable for the ease with which they can be worked into bowls, cups, and similar round objects. Horsford hypothesized that the burls were harvested in the forests and floated down to the Charles in canals, for which he claimed to have found physical evidence. |

|

|

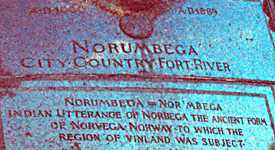

Horsford wrote extensively about his hypotheses. In addition, he summarized his conclusions in a stone tablet in his Norumbega monument. After his death, his daughter continued publicizing and writing about his work. Articles appeared in popular publications as diverse as National Geographic and Popular Science Monthly. Popular travel books of the day guided tourists to the important Norse sites described by Horsford along the banks of the Charles River. |

Contemporary historians gave little credence to Horsford's theories or his evidence. Other public figures supported him. But as the years passed, and no actual artifacts were produced from any of the sites, it became harder and harder to accept Horsford's conclusions seriously. By the beginning of the 20th century, even his early ardent supporters dropped their support.

References:

[1] Richard R. John, "Eben Norton Horsford, the Northmen,

and the Founding of Massachusetts", Essays on Cambridge History,

Proceedings, 1980-1985. Cambridge Historical Society, 1998.

[2] Eben Horton Horsford, The Landfall of Leif Erikson A.D. 1000 and the

Houses in Vinland. Damrill and Upham, 1892.

Thorvald's Rock

Hampton, New Hampshire

Grćnlendinga saga (chapter 4) says that Ţorvaldr Eiríksson led an expedition to Vínland. While there, he and his men battled with Skrćlingjar (native Americans). Ţorvaldr was wounded by an arrow and died there. Before he died, he asked to be buried near the headland, which he wanted to be known as Krossanes.

|

Where is Krossanes? Some people in Hampton, New Hampshire, believe that the Boar's Head promontory (left) at the northern end of Hampton Beach is Krossanes, and that the stone on display at the Tuck Museum is Ţorvald's grave marker. |

|

The stone has scratches on its surface which have been interpreted as runic characters. |

|

|

References to the stone appear as early as the 17th century, when Hampton was settled. The stone originally rested near the end of what is now Thorwald Avenue. |

|

|

Souvenir hunters chipped away at the stone for years. In 1989, it was moved to its present location at the Tuck Museum, where it was placed in a protective barred cement well. |

Is it the Ţorvald's grave marker? Unlikely.

|

Hampton does not match very well with the description in the saga. Krossanes is described as a headland between the mouth of two fjords. Before the Skrćlingjar attack, it is said they swarmed down one of the fjords towards Ţorvaldr and his men. Hampton has nothing remotely like a fjord in its vicinity, and it seems unlikely that two of them have vanished in the intervening 1000 years. The language in the text suggests that before landing, Ţorvaldr was sailing eastward along a north-facing coast. Hampton Beach faces east. |

|

|

Prior to the attack, Ţorvaldr called the site beautiful and said he wanted to build his farm there and remain for the rest of his life. The marshy area that exists today just inland from the beach does not seem like a very good place for a farm. |

|

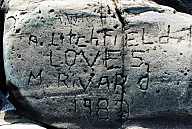

The runic carvings on the rock require a great deal of imagination to interpret. If one walks on the boulders near Boar's Head, one can easily find a dozen more specimens where glacial scratches look vaguely like runic characters (left) as well as countless modern "runic" inscriptions (right). |

|

Over the years, there has been at least one attempt to dig for Ţorvald's remains at the original site of the rock. Nothing has been found, which is not surprising, since the soil conditions at the site are not at all conducive to the preservation of materials.

|

The poor match between the saga description and the geography of Hampton, combined with the dubious runic inscriptions make it unlikely that Krossanes was located in Hampton. A more plausible location is in Newfoundland, or possibly in Nova Scotia. Kelly Point, on the north side of Cape Breton Island, is a headland between two fjords. |

|

|

While Thorvald's Rock makes for an interesting tourist stop in Hampton, it seems unlikely that Hampton was the final resting place for Ţorvaldr Eiríksson. |

References:

The

Lane Memorial Library in Hampton maintains a nice collection of on-line resources

related to Thorvald's Rock, and the Hampton Historical Society has a brief

discussion of the rock, and other

monuments at the Tuck Museum.

Dighton Rock

Berkley, Massachusetts

Until the end of the 20th century, Dighton Rock has rested in the mud of the Taunton River in Massachusetts, fully submerged except at low tide. The rock is a sandstone bolder, a block approximately 1.5m high, 2.5m wide, and 3.4m long (60 x 115 x 130 inches). One side of the block is covered with inscriptions. At low tide, the inscriptions would have been visible to anyone in a boat on the Taunton River. Sketches of the inscriptions exist from as early as the 17th century, so the inscriptions are clearly historical, rather than a modern hoax. |

|

In the 17th century, an American scholar interpreted the inscriptions as having been made by Indians. In the 18th century, a French scholar interpreted the inscriptions as Phoenician. In the 19th century, a Danish scholar interpreted the inscriptions as Norse. In the 20th century, an American scholar interpreted the inscriptions as Portuguese. I'd like to add my own 21st century interpretation, and suggest the inscriptions were made by bug-eyed aliens. The evidence would seem to support any of these theories equally well.

It's not surprising that scholars can't agree on the origin of the inscriptions; none of the the sketches made over the last three centuries resemble one another, as if even the artists couldn't agree on the appearance of the inscriptions.

|

The first known photograph of the rock was taken in 1853. To enhance the inscriptions for the photograph, the inscriptions were filled in with chalk. |

|

|

Unless special lighting techniques are used, the inscriptions today are barely legible. |

What is the probable origin of the inscriptions? I think we can safely reject the suggestion of a Norse origin put forward by Carl Christian Rafn in 1837. Rafn used a sketch provided by the Rhode Island Historical Society, and he is not known to have visited the site to inspect the rock first hand.

Rafn believed that the inscription related to the voyage of Ţorfinnur karlsefni to Vínland, described in both Eiríks saga rauđa and in Grćnlendinga saga. Using characters that are not apparent in the original sketch, Rafn interpreted the text on the rock to read "Ţorfinnur and his 151 companions took possession of this land."

This explanation seems unlikely on several counts. The rock and the inscriptions are very different from stone inscriptions in Scandinavia known to have been created at the time when Ţorfinnur and other Norse explorers were thought to be visiting Vínland. More significantly, Rafn's description of the inscriptions on which he based his interpretation differs considerably from the sketch he is known to have used. One wonders how much wishful thinking he used in generating his interpretation.

To his credit, Rafn's book, Antiquitates Americanć, is the first scholarly book to suggest that Norse explorers reached North America, as described in the sagas.

|

In 1963, the rock was raised from the riverbed, and in 1973, a museum was built around the rock on the shore of the Taunton River. The museum is located in the Dighton Rock State Park. |

|

Viking Tower

Newport, Rhode Island

by Ron Black

On

a hillside that overlooks Narragansett Bay in Newport, Rhode Island, sits a curious structure:

a stone tower. Normally such a structure would not be so shrouded in mystery, but the

discovery of a rune marker stone on one of the legs of the tower has created years of debate. The

tower at Touro Park was thought to have been owned by Gov. Benedict Arnold (grandfather of the

famous traitor) until the discovery of the rune stone in 1946. Over the past 50 years an impassioned

debate has continue to rage over the origin of the tower.

On

a hillside that overlooks Narragansett Bay in Newport, Rhode Island, sits a curious structure:

a stone tower. Normally such a structure would not be so shrouded in mystery, but the

discovery of a rune marker stone on one of the legs of the tower has created years of debate. The

tower at Touro Park was thought to have been owned by Gov. Benedict Arnold (grandfather of the

famous traitor) until the discovery of the rune stone in 1946. Over the past 50 years an impassioned

debate has continue to rage over the origin of the tower.

Some

believe that the five runic markers read 'HNKRS' representing the old Norse word for stool,

meaning the seat of a bishop's church [1]. In 1948, an archaeological dig was

begun and concluded in 1949. The dig turned up no evidence pointing towards

Norse colonization of Rhode Island. In fact, it did just the opposite. Over

twenty items of colonial American origin were found,

including clay pipe fragments, a gunflint, colonial pottery, and a shoe imprint

[2,3] of a colonial style in the hard clay earth. The findings of this dig are all

secured at the Peabody Museum.

Some

believe that the five runic markers read 'HNKRS' representing the old Norse word for stool,

meaning the seat of a bishop's church [1]. In 1948, an archaeological dig was

begun and concluded in 1949. The dig turned up no evidence pointing towards

Norse colonization of Rhode Island. In fact, it did just the opposite. Over

twenty items of colonial American origin were found,

including clay pipe fragments, a gunflint, colonial pottery, and a shoe imprint

[2,3] of a colonial style in the hard clay earth. The findings of this dig are all

secured at the Peabody Museum.

There are several possible reasons for the absence of

Norse artifacts on the site of the tower. Extensive farming of the area by the

colonists may have unearthed and destroyed any sizeable artifacts. In addition, new

construction prior to the dig may have disturbed the area.

Another curiosity of the tower is its strange

construction, which resembles that of a tower built in Warwickshire, England (right) on the farmstead of a

young Benedict Arnold. However, some interior features (left) are thought to more

closely resemble a Norse

religious structure. The eight legs of the tower sit exactly on the

points of the compass. According to the legend of the tower, the

stone structure was built to replace a wooden mill, which blew down during a storm.

Some experts believe that if this were true, the new stone tower

would have been built quickly due to the need to produce food, thus the pinpoint

accuracy of the towers position would be impossible or sheer luck. Another

puzzling item is a fire place which sits too high for cooking and is too shallow to provide

any substantial heat, but is ideal for a beacon fire which could have been seen

from the bay through the large window opposite the fire place. Other sources say

that the fireplace is of a more religious nature providing a ceremonial fire that,

according to custom, was never to go out [1]. On either side of the fireplace are

recessed areas ideal for the placement of holy figures or other items.

Another curiosity of the tower is its strange

construction, which resembles that of a tower built in Warwickshire, England (right) on the farmstead of a

young Benedict Arnold. However, some interior features (left) are thought to more

closely resemble a Norse

religious structure. The eight legs of the tower sit exactly on the

points of the compass. According to the legend of the tower, the

stone structure was built to replace a wooden mill, which blew down during a storm.

Some experts believe that if this were true, the new stone tower

would have been built quickly due to the need to produce food, thus the pinpoint

accuracy of the towers position would be impossible or sheer luck. Another

puzzling item is a fire place which sits too high for cooking and is too shallow to provide

any substantial heat, but is ideal for a beacon fire which could have been seen

from the bay through the large window opposite the fire place. Other sources say

that the fireplace is of a more religious nature providing a ceremonial fire that,

according to custom, was never to go out [1]. On either side of the fireplace are

recessed areas ideal for the placement of holy figures or other items.

Evidence from the site of the tower points to a colonial time frame. However, the tower appears on two maps predating the colonial era by over half a century. Giovanni da Verrazano mapped the area in approximately 1524 and listed the tower on his map and in his logs as a "Norman Villa". In addition, Mercator's map, circa 1569, also shows the exact location of the tower.

Some of the best evidence comes from 14C dating of mortar taken from the tower in 1993. AMS (accelerator mass spectrometry) analysis of the samples yielded a date of about 1680. The construction materials (mortar and field stone) closely resemble those of other 17th century structures in Rhode Island.

Though there is evidence on both sides of the argument, Norse and Colonial, the

hard evidence points to a colonial origin for the tower.

References

[1] Early Explorers of North America, C. Keith Wilbur, 1989.

[2] Frauds, Myths and Mysteries, Kenneth Feder, 1996.

[3] Vikings, The North Atlantic Saga, Smithsonian Inst Press, 2000.

Norumbega, a Norse Colony in New England?

by Ron Black

Is there evidence linking Rhode Island to Vínland or another Norse colony? Paul H Chapman, author of the article "Norumbega: A Norse Colony In Rhode Island" [1], believes that the Norse settled in Rhode Island, and that after voyages to Vínland ended, they became the Narragansett Indians, emulating the styles and ways of other native Americans. However, the evidence is more speculation and hearsay than hard fact.

Chapman's cultural evidence includes the stature and skin color of the Narragansett Indians. Verrazano, who explored the area in 1524, describes the natives as "excelling us in size" and "…are of bronze color, some inclined more to whiteness…the face sharply cut". Notably, the Norse of the time (and today) are described as having sharply cut faces. To some, this could be seen as grasping at straws, but Roger Williams, founder of the Rhode Island colony, lived among the Narragansetts and reported roughly the same. Williams also recorded that the natives children were often born with white skin and red hair. He went on the say that their skin darkened from a life out doors and that their hair was dyed a darker color as they got older.

Chapman's other evidence is the advanced agricultural activaties of the Narragansetts. The other area tribes practiced nomadic hunting, while the Narragansetts lived and farmed in permanent communities, using hunting as a supplement for gathered food. The farming practices of the Narragansetts cannot be attributed to colonial era guidance since the colonists learned their farming practices from the natives.

Chapman has interpreted the name Narragansett to mean Northman settlers. He breaks the name down in this way; Nar short for NORman, stating that the Old Norse often used A for O during the development of the language, gan being the Old Norse for gang meaning walk, and sett to settle.

Existing historic and cartographic records also provide evidence of Norse settlement in this area. Two early cartographers of North America, Verrazano (1524) and Mercator (1569), place the Viking Tower of Newport, RI on their maps. While Verrazano called this location a "Norman Villa", Meractor showed the name "Norombega" as the name of this location. Mercator and other cartographers used this name for both the region and location of a local community on Narragansett Bay. The name Norombega has been broken down this way, according to Chapman: Nor meaning for Norman; um for all over; and beg for Bygd meaning an inhabited land in Old Norse. The a, at the end of the word would also be a typical suffix for Old Norse words. Other place names hailing the Nor- prefix can be found in the surrounding area. While some come from England, others are old Indian names for these areas.

Chapman's third source of evidence is the over one hundred rune stones found in New England. Three of these were found in Narragansett Bay. To this date only one has been proven a forgery, according to Chapman. He claims that the general position of the "Establishment" is that the only Norse settlement in North America was L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland. Therefore the stones found elsewhere must be fake, thus the historical community has concluded: no artifacts, no evidence, no presence.

References:

[1] Chapman, "Norumbega: A Norse Colony In Rhode Island", The Ancient American 1994.

|

|

©1999-2025 William R. Short, portions ©2001 Ron Black |