|

|

Longhouses in the Viking Age

Throughout the Northern lands in the Viking age, people lived in longhouses (langhús), which were typically 5 to 7 meters wide (16 to 23 feet) and anywhere from 15 to 75 meters long (50 to 250 feet), depending on the wealth and social position of the owner. In much of the Norse region, the longhouses were built around wooden frames on simple stone footings. Walls were constructed of planks, of logs, or of wattle and daub.

|

In Norse regions that had a limited supply of wood, such as in Iceland, longhouse walls were built of turf. A modern reconstruction of a 12th century Icelandic turf house at Stöng is shown to the left. (More details about turf house construction and architecture are in a separate article on turf houses.) |

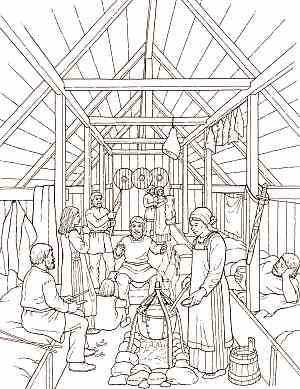

Inside, the longhouse was divided into several rooms. Two rows of posts ran down the length of the longhouse supporting the roof beams. These columns divided each interior room into three long aisles. The columns supported the roof, and, as a result, the walls supported little weight. Typically, the walls bowed out at the center of the longhouse, making it wider in the center than the ends, mimicking the shape of a ship.

|

The central corridor of each room, between the row of roof support columns, had a packed dirt floor (right). Ashes from the fires of the house were spread on this area to act as an absorbent. In the Viking-age house at Hofstaðir in north Iceland, slag and hammerscale have been found in this floor layer, suggesting that ashes from the hearth in the smithy were also brought in and spread on the floor in the house. Hofstaðir also had clear evidence of mice living in and around the floor of the longhouse. This central aisle was the passageway between sections of the house. In addition, fires were built in this region, either in a fire pit running lengthwise in the longhouse (left), or in individual fire circles in the rooms. The fire provided light and heat and was also used for cooking. |

|

|

Some houses, such as at Aðalstræti 14-16, had a large and imposing hearth, with stones set on end in the earth, mirroring the shape of the longhouse. The firepit at Vatnsfjörður (left) also follows this form, reflecting the outline of the house. The stone firepit is in the central foreground, and the outline of the walls is made visible in the turf by rise created by the foundation stones still buried just below the surface. In contrast, the firepit at Hofstaðir was surprisingly small, inadequate for the size of the house. The evidence suggests that the house was not usually fully occupied, and that the additional space was used for occasional guests during feasts and celebrations. Some of the stone hearths have compartments built into them, perhaps for keeping food and other items warm, or perhaps for storing tools and other utensils used for the fire or for cooking. |

|

A feature found in the longhouse at Vatnsfjörður is a stone-lined pit in the floor (right, and visible beyond the firepit in the photo above left). The pit contained refuse and may have served as the trash-can for the house. The pit also contained a small piece of gold jewelry, suggesting that the piece was lost on the floor and inadvertently ended up in the trash pit. |

|

|

Smoke holes in the roof (or, in rare cases, chimneys) provided ventilation and illumination, letting in light and letting out smoke. |

|

On either side of the central corridor (between the roof support columns and the walls), raised wooden benches topped with wooden planks ran the length of the longhouse. They provided a surface for sitting, eating, working, and sleeping. |

|

Typically, no windows were used in the house. All light came from smoke holes overhead, and open exterior doors. Some houses may have had small openings covered with animal membranes, located where the roof meets the wall, to allow more light to diffuse into the house. Gunnar's house at Hlíðarendi is described as having windows near the roof beams protected by shutters (Brennu-Njáls saga, ch.77).

|

Additional light was provided by simple lamps, made from readily available materials. The photo to the left shows a Norse era lamp made from a dished stone, which was filled with fish liver oil for fuel, or, when available, seal or whale oil. Fífa (cottongrass, or Eriophorum), a common weed (right), was used as a wick. |

|

|

A modern reproduction of a lamp using cod liver oil and cottongrass provided much better light than anticipated. The light was steady and surprisingly bright, with little smoke or odor. The light is sufficient for doing detailed handwork, and even for reading. |

|

Candles were not unknown, but were expensive and thus infrequently used. Candle holders of various types have been found from this era, but typically in churches. When candles are mentioned in the sagas, it is typically a priest who holds them.

Windows had other uses, as well. One night, Grettir fought off twelve Vikings outside the house where he was staying as a guest, as is told in chapter 19 of Grettis saga. The farmer's wife had lights put in the windows so Grettir could find his way back to the farmhouse in the dark.

With their limited ventilation, one might think that these houses would have been smoky, dim, and murky, as is usually depicted in modern illustrations of longhouses. But, I've been amazed by how bright the interiors were of the longhouse reconstructions I've visited. The longhouse photos on this page were shot using only the natural light filtering in from the smoke holes and doors.

When I visited the Stöng farmhouse for the first time, I was just as amazed at how dim and dismal the interior was. Only during a later visit to Stöng did I discover the reason for the difference: the smokeholes at Stöng were closed when I first visited. When the smokeholes were opened, Stöng was just as bright as any of the other longhouses.

However, the saga literature suggests a dim interior. For example, in chapter 28 of Grettis saga, Auðun, entering the dim longhouse from outdoors, was unable to see Grettir, who intentionally tripped him. That episode is quite believable in a house as dim as Stöng was on my first visit.

|

Since no longhouses from the period survive, it's unclear what their ventilation scheme might have been. The longhouse re-creation at L'Anse aux Meadows apparently had the smoke holes placed incorrectly in the roof of the longhouse. (The smoke holes have subsequently been moved, since when I visited.) Said one of the re-enactors, "Some days you can't see from one end of the house to the other through the smoke." |

|

|

I experienced that condition during a visit to Eiríksstaðir. A poorly lit fire filled the house with smoke (left), despite the open smokehole overhead (right). In the Viking age, drafts were avoided in the house by using antechambers and double doors that formed airlocks. Drafts not only could chill the house, but also could spoil the normal draft of the fire, filling the house with smoke. |

|

|

Typically, the longhouse reconstructions were surprisingly cozy and pleasant. The wooden bench topped with a sheepskin made a comfortable seat for lounging. The fire kept things warm, dry, and toasty, and was conveniently near at hand from the bench. At L'Anse aux Meadows, sunlight pouring in through the smoke holes brightened up the interior in a cheery way. One easily can imagine people comfortably sitting, cooking, eating, drinking, and working on chores in the longhouse. |

|

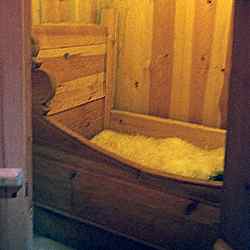

It is unlikely that the longhouses had much furniture. Only the master and mistress of the house would have had a box-bed in which to sleep, usually located in an enclosed bed-closet. The remainder of the household slept on the benches. Most re-enactments show people sleeping lying down on the benches between layers of sheepskin. However, surviving beds and reconstructed bed-closets and benches are extremely confining, suggesting that Viking-age people may have slept sitting up on the benches, with their backs against the wall. Laxdæla saga (chapter 7) says that in her old age, Unnr in djúpúðga (the deep-minded) died in her sleep. She was found by her grandson the next morning sitting up among the cushions. |

|

|

Beds were probably lined with straw. An interpretation of an open bed at Eiríksstaðir is shown to the left. It's lined with straw and covered with an animal skin. Weapons hang from the wall behind the bed. |

|

An interpretation of the bed in the bedcloset at Stöng is shown to the right. The bed cover is sheepskin. It's possible that some people used wool blankets as bed covers, or even wool blankets stuffed with down. In chapter 27 of Gísla saga Súrssonar, Gísli hid from his pursuers between the straw and covers of the bed of Refur and Álfdís. Álfdís got into bed on top of Gísli. When Gísli's pursuers entered the house to make a search, Álfdís showered them with abuse, which kept them from examining her bed very closely. Droplaugarsona saga (chapter 9) says that Þorgrímr and Rannveig slept under a wool bed cover. One morning before breakfast, Rannveig declared herself separated from her husband Þorgrímr. Before she left, she threw all of his clothes into the sewage pit. Þorgrímr wrapped himself in the woolen bedcover and went to the neighboring farm for help. |

|

Very wealthy people may have had much finer bedding. In chapter 51 of Eyrbyggja saga, Þórgunna's bedding included fine English sheets, a silken quilt, and pillows.

|

Some of the stories refer to sleeping quarters in the loft of the longhouse. (For instance, in chapter 77 of Brennu-Njáls saga, it is said that Gunnar slept in a loft above the hall, together with his wife and his mother.) However, the upper levels of a longhouse, besides being dark and cold, must also have been foul with smoke from the open fires, making it unlikely that anyone would want to sleep there. At Eiríksstaðir, a ladder (left) leads up to the very dark and smoky sleep loft (right). |

|

|

Foodstuffs were probably stored and prepared in a pantry (matbúr), then brought out to the fire in the main room for cooking. An outside storage room (útibúr) stored food, as well as other valuables. |

|

|

Stories refer to tables being set up for meals, then taken down for other activities. It's not clear what form those tables might have taken, but they were probably trestle tables. It's possible that trestles, boards and additional benches were stored overhead, lying on the cross beams, and brought down for meals and feasts. The other likely pieces of furniture in a longhouse were wooden chests for storage and a vertical loom for weaving cloth. The loom and one of the tables at Stöng is shown to the right. |

|

|

It's been suggested that the space under the bench was used for storage of spinning and weaving materials, along with finished goods. The cross bench at Stöng is shown to the left, with one of the seating planks lifted to reveal the storage space. |

|

It's unlikely that chairs as elaborate as the reconstruction shown to the left were ever common. The original is from 12th century Norway. The sagas occasionally mention chairs. Chapter 23 of Fóstbræðra saga says that Gríma had a chair carved with a likeness of Þórr and his hammer. Simple three-legged stools, such as the reproduction shown in the top photo to the right, were probably much more common. People also used their wooden storage chests (lower photo, right) as seats. |

|

|

A modern reproduction of a chest is shown to the left. The chest incorporates an internal locking mechanism. The teeth on the key (right) rotate into holes on an internal locking bar, releasing a spring latch and allowing the key to slide the locking bar to the open position, freeing the hasps from the inside and unlocking the chest.. |

|

|

Houses of wealthy families probably had decorative wall hangings, or carvings, or possibly paintings. The sagas tell of elaborately decorated shields hung on the walls (Egils saga, ch. 78) and tapestries hung to decorate the hall for feasts (Gísla saga Súrssonar, ch. 12). A modern replica tapestry is shown to the right. In chapter 29 of Laxdæla saga, it is said that in Ólaf's hall at Hjarðarholt, the wainscoting was decorated with scenes from the Norse myths. |

|

|

Despite the cozy picture I've painted above, the longhouse was scarcely the place for privacy. The entire extended family did everything here: eating, cooking, dressing, sleeping, work, and play, both day and night. Everyone must surely have known what everyone else was doing. Privacy did not exist; modesty must have been unknown. |

|

In chapter 75 of Grettis saga, there is an episode that illustrates the lack of privacy. Late in the day, Grettir swam from his island hide-away to Reykir, Þorvald's farm on the mainland (shown to the right as it looks today). It was after dark, and the people of the farm were asleep. Grettir bathed in the hot pool, then went into the house and fell asleep. In the night, his bed clothes fell off of him. |

|

The first to arise the next morning were Þorvald's daughter and a servant-woman. They saw Grettir lying naked, asleep. The servant said, "Grettir the Strong is lying here, naked. He's big-framed, all right, but I'm astonished at how poorly endowed he is between his legs. It's not in proportion." The two of them took turns peeking at Grettir and laughing at what they saw. Grettir awoke and returned their insults with some bawdy poetry.

|

It is possible that some houses were protected by fortifications (virki) built around the house. Fortifications are frequently mentioned in the contemporary sagas, set in the turbulent Sturlunga Age at the end of the 12th century through the beginning of the 13th. Fortifications are less commonly mentioned in the family sagas, set in Viking-age Iceland. In Eyrbyggja saga, it is said that Óspakur had a fortified farm at Eyrr (shown to the left as it appears today). Óspakur, his men, and a Viking named Hrafn, stole, plundered, and killed all throughout the region. In chapter 62, Snorri goði and his men attacked Eyrr. Óspak's men threw stones from atop the fortification to hold off the attack. From the outside of the fortification, Þrándur took a running leap and hooked his axe over the top of the wall. He climbed hand over hand up the shaft and entered the fortification, where he cut off Hrafn's arm. |

A recently-excavated Viking-age site (right) shows evidence of a very broad wall at the periphery of the site. The stones forming the foundation of the wall are 2m apart (7 ft) and were filled with turf between them. This breadth suggests that the wall was also very tall, much taller than what is needed for keeping out animals. Perhaps this wall was the fortification for the house. |

|

|

Archaeological and literary evidence suggest that some houses may have had other unusual features. In the summer of 2002, an interim report was released by archaeologists working at Reykholt (left), one of the farms belonging to Snorri Sturluson in the 13th century. Stone structures were found underneath the longhouse which have been tentatively interpreted as an underground heating system fed with hot water from a nearby hot spring, a development that certainly would have made life in the house much more pleasant in winter. Króka-Refs saga (ch.12) says that Ref's home in Greenland used underground wooden pipes to supply water from a nearby lake to the house and fortification in order to foil his enemies' attempts to burn down the house. No physical evidence of such structures has been found, and the limitations of the digging tools available during the Viking age would seem to make such underground engineering efforts nearly impossible except in the most favorable possible circumstances. |

Archaeological evidence and saga evidence suggests that most house sites also had a number of smaller outbuildings used for a variety of purposes, including food and fodder storage, iron working, textile working, and other purposes.

In a new article on the importance of seating in the Viking-age longhouse, we dive deep into this topic, and into how one's seat in the house reflected one's place in society.

In summer, 2024, Hurstwic held a Fire Festival at the Viking house at Eiríksstaðir where we used experimental archaeology to research the Viking-age battle tactic of burning down the house. At this time, the data analysis is incomplete, but we have issued a preliminary report video showing how the fire moves in a burning longhouse.

|

|

©1999-2026 William R. Short |