|

|

The Saga of Hurstwic:

Told by William R. Short

This page tells the story of Hurstwic's journey to this point in time. It is a journey that was filled with twists and turns, with many dead ends and pitfalls, but also great victories, discoveries and true and honest fellowship. This page is the back story of how we came to the conclusions in our new book, Men of Terror. It maps the unmarked road we walked in our quest to learn how Vikings lived, fought, and died.

Here is our story: the Saga of Hurstwic.

One: From the emptiness of the void, the journey begins

|

|

Hurstwic began life as an historically accurate living history group, started by Ron Black and Casey Dorman. The name Hurstwic was chosen based on Anglo-Saxon placenames but has no meaning other than that. Prior to this time, my background was as Doctor of Science conducting research related to sound, acoustics, human hearing, and other fields. I received dozens of patents and was jointly awarded the IPO Inventor of the Year award in 1987. I joined Hurstwic after taking a summer course on the sagas in Iceland. I had only just learned about these stories of Viking-age people and was fascinated by the stories and eager to learn more. I cannot say why these stories grabbed my attention so strongly. Perhaps because the sense of humor of the saga characters so closely matches my own: cold, dry, and understated. |

|

The summer course only served to fuel a curiosity and desire to learn more about the people of the sagas: their daily lives; their material culture; their beliefs and values. I wanted to extend my study of the sagas by doing some hands-on research, particularly in the area of combat. Only later did I learn that combat was perhaps the least explored and researched area related to Vikings and, at the same time, combat carried far more weight in understanding the Viking people than I imagined. Yet, there was a problem: I was in no way an experienced fighter. Even so, as a professional researcher, I thought I had something to offer to the group.

Just prior to my joining the group, there had been an injury during Hurstwic weapons training. I did not want another injury in any group with which I was affiliated, so I took it upon myself to find a better way to train.

Although Hurstwic was affiliated with Regia Anglorum, the lines of communication to their experts in the UK were very tenuous. The closest other North American member was many hundreds of miles away and feeling just as isolated as we. So, the journey continued, and I searched elsewhere.

I discovered some material on-line published by HACA (now known as ARMA). The site described how to make training weapons that we could use for Viking training which seemed to reduce the risk of serious injury. We made weapons according to their patterns and started to use them. But we still didn't know how to train nor how to fight. We were enthusiastic and eager, but there was nothing to distinguish us as Vikings, except perhaps for the clothes we were wearing and the pattern of our weapons. We were only making up how Vikings fought because we had nothing to use as a source. In some sense, we were just playing dress up. |

|

|

At the same time, I was using my scientific background to do some ground-breaking testing on Viking ice skating, and on knattleikr, the Viking ball game. Additionally, we were doing some very interesting experiments with Viking food and with detailed nutritional studies of Viking diets with Dr. Sarah Short of Syracuse University, a biochemist specializing in nutrition and sports nutrition. |

Two: The trap of techniques / we thought we knew it all

Even though we didn't know what we were doing, we were intent in pursuing our goal of understanding Viking combat. I searched for people who could help us train. More traditional martial arts schools based on Asian systems didn't seem appropriate. Interest in historical European martial arts was only beginning to bloom, and there were no groups near us doing regular work.

|

One of the places I contacted was Higgins Armory Museum, a museum of arms and armor in Worcester, MA, USA. (Sadly, the museum closed its doors at the end of 2013.) The new curator, Dr. Jeffrey Forgeng, was starting a group to research and practice medieval and Renaissance fighting as taught by the historical combat treatises. Dr. Forgeng would later become world-renowned for his translations and interpretations of these manuals. I immediately joined the group, which took on the name Higgins Armory Sword Guild. |

|

I was pleased to be working with a group that had a training plan and a focus, even if that focus was not the same as my own. Studying at Higgins also gave me the opportunity to study the artifacts and weapons of the medieval age up close and personal. This study showed me how improvements in metallurgy and technology over the centuries allowed better weapons and better armor, resulting in a change in how the weapons were used. |

|

|

At the Sword Guild, we started our training with Meyer's treatise. At the same time, we were also working on sword and buckler material from the Royal Armouries I.33 manuscript. It seemed like the material taught there ought to be applicable to Viking sword and shield. |

|

I.33 is the treatise closest to the Vikings: closest in time (perhaps two or three centuries after the close of the Viking age); closest in place (from lands now part of Germany); and closest in weapons (sword and buckler). It was easy to believe at first that because of these close connections, Viking-age fighting must have resembled that taught in I.33, or at the very least, that I.33 must retain faint echoes of Viking sword and shield fighting. |

|

At the same time, Hurstwic was foundering. It became harder and harder to schedule group events, and the dissension building between members made events less enjoyable for all. Both of the founders withdrew because of family reasons, and the remaining members chose to disband, rather than to continue. In some small way, the end was almost a relief, because it was now easy to drop it and to move on to other things. |

|

|

I had created a substantial web presence for Hurstwic, material which seemed to be genuinely useful to students of the Viking age around the world. I decided to maintain the website using the Hurstwic name, and to build and grow the material to make it a destination for anyone with an interest in the Viking age. |

Three: Fellow travelers

|

My study of Viking-age weapons and their use had reached a point where I felt comfortable doing a regular monthly presentation on Viking arms and armor at Higgins Armory Museum for museum guests. One of the early guests was Matthew Marino. His interest in the Viking age grew out of his interest in historical Anglo-Saxon wood-working techniques. Matt joined me in my research of Viking weapons and their use and then subsequently joined me in the demos. |

|

|

This event was a milestone in Hurstwic's journey. Matt brought a deep knowledge and practical experience in how Viking-age people made things out of wood, iron, leather, fabric, and other materials. He also brought a different mindset and approach to our weapons training: a practical and open-minded approach to the work that accelerated our training and greatly improved our demo material. Working together, Matt and I were able to accomplish much more than I had been able to accomplish working on Viking material alone at the Sword Guild. |

Our research continued along these lines at the Higgins Armory Sword Guild, and several more people joined in our Viking practice and in our demos. |

|

Four: Realizing we might be lost

|

About this time, I became much more curious about what the Sagas of Icelanders taught us about Viking combat. By this time, I had read all of the sagas in English translation, and some of the sagas in the original Old Icelandic. It became more clear that there was a lot of useful information in the sagas. Earlier, some researchers had pulled out a dozen or so examples of Viking combat, using antiquated English translations. I felt there were many more examples to be found in the sagas, and I strongly felt that using the original Old Icelandic was essential to tease out the exact meaning of the texts. I created a concordance of all of the references to weapons, armor, and fighting in the Sagas of Icelanders. This reference proved to have value far beyond our expectations, not because of any one episode related in the sagas, but rather because of the accumulated weight of episode after episode that described Vikings in conflict. This evidence planted seeds of doubt in my mind that the fights described in the Sagas of Icelanders resembled the fights taught in the later combat treatises. |

Doing this work required me to read and re-read all the saga passages relating to weapons, armor, and combat both in English and in the original Old Icelandic. In addition, I looked at a number of related works, such as the kings' sagas (Heimskringla) and contemporary sagas (Sturlunga saga) in both English and Old Icelandic. This work made me much more familiar with the sagas and what they say about combat and weapons.

Comparison of the fight descriptions in Sturlunga saga and in the Sagas of Icelanders made it seem more likely that the Sturlunga-era authors of the sagas were aware of the differences in weapons and moves between their own time, when the sagas were written, and the Viking-age, when the sagas were set.

Around this time, I realized that bioarchaeological evidence would be valuable in our research. We began studying the archaeological reports that described Viking-age skeletal remains with battle injuries. These reports told us about targets, weapons, injuries, and even damage to weapons. |

|

|

At this point, the ground work for our continuing research was in place. We felt that our research stood firmly on three legs: on the combat treatises, the sagas, and bioarchaeology. Around this time, I decided to write a book that described our research and expressed our thoughts on Viking weapons and their use. Viking Weapons and Combat Techniques was published in 2009 by Westholme Publishing. |

Five: The Emperor's new clothes became yet more revealing

|

|

Throughout this time, I continued to visit Iceland on a regular basis to continue my research on the sagas. I sought out experts in many fields. I learned from the archaeologists excavating Viking-age sites in Iceland. I learned from men and women who were experts on a particular saga because they had been born and lived their entire lives in the valley or fjord where the saga took place, and so could show me every site where key episodes in the saga occurred. I learned from men and woman who grew up in Iceland before modernization who could teach me the skills that would have been a part of Viking-age living, such as how to find and cut the best turf, or how to find one's way when there is no map. These special advisors to Hurstwic's research have been priceless. |

|

I found the old travel routes and experienced them for myself to help understand why key events in the sagas took place where they did, far from modern roads and settled areas. I visited the sites of battles mentioned in the sagas to study them. In some cases, the landscape has changed so little since the battle that it is possible to visualize every move of the combatants as described in the saga. Even in places where there have been dramatic changes to the landscape, the echoes of events from the sagas can still be clearly heard. |

|

The one group that was not so keen on being associated or assisting with Hurstwic's work were the academics who were researching Vikings at the universities. They were a group that had mostly locked their doors to the communities of reenactors and non-academic researchers, an on-going theme as we progressed in our journey.

|

After the Viking weapons book was delivered to the publisher, but before it was released, I was invited to present a public lecture on the book at Háskólasetur Vestfjarđa (The University Centre of the Westfjords) during my next visit. News of the lecture reached the national press in Iceland, and I was asked to give another lecture in Reykjavík, later in the same visit. One member of the audience was Reynir A. Óskarson, a man with broad and deep experience in a range of fighting skills and training approaches. After I returned home from Iceland, I received an e-mail note from Reynir, asking a few probing questions about the material in my lecture. That note was the start of a fruitful collaboration. |

Reynir was born and raised in the land where the sagas took place, and like all Icelanders, he was exposed to the sagas in school and while traveling the landscape of his homeland. Additionally, he had fighting experience and training that was both deep and broad. But his interests did not strongly lean towards Viking-age history and culture, or to the saga literature. Nor had he studied the combat treatises that I had been using as a source. In many ways his mind was not trapped by the well-worn path of Viking combat set by modern reenactors and explorers. |

|

Reynir is a master of the Socratic method. He did not let me get away with using flimsy evidence, instead asking probing questions about my conclusions, starting in that first e-mail exchange. Perhaps he thought it strange I was using a source so far removed from Viking times and Nordic lands, and he asked questions for which I had no good answers. And perhaps my beliefs about the treatises were not as firmly-held as I thought, because as we Sword Guild Vikings practiced, we were finding more and more discrepancies between the treatises and sources more closely related to Vikings.

Six: The limp leading the blind

During my regular visits to Iceland, Reynir and I would have long discussions and long hours of training and exchanging ideas. Reynir is an intense goal-oriented man like me, but as he told me, he was very scared that his previous background in combative training would taint the goal of understanding how Vikings fought, in much the same way that I felt that the combat treatises had tainted my goal. It is easy for the modern concepts of efficiency in combat to influence our research and distort our results.

|

Reynir and I came to the understanding that with the combination of his martial arts experience, my scientific background and the resources of the people associated with us, we could actually do some very interesting research as long as we questioned each and every source. Reynir stated it most clearly when he said the training room is sacred; it is a laboratory where tests are done. People who are peeking through the window of the training room should see clearly that these are people doing Viking fighting even if the researchers were wearing pajamas and armed with Swiss army knives. The attire and weapons would not be what defined us as Viking fighters and researchers, but rather the moves being performed. This thinking was unique and unconventional, and contrary to anything else I had heard at that time. We devised a new approach to training based on complete freedom. We use only basic kinesiology and science to test the sources to learn what Viking combat really looks like. We use the data we obtain from our tests to do the next series of tests. We were doing science, taking advantage of my years of experience in this area, rather than blindly following what was written in a book. |

It became immediately clear that the traditional training approach based on the treatises that we had been using had very limited utility compared to this new approach to training and research. The new approach added life and energy that vitalized the practice room and lifted the spirits so that people were eager to come back for more. Drills had a purpose that was clearly articulated to students. Our drills became flexible and improvisational, so that they could be easily adapted to the needs of the moment, and so that we could easily research the areas we most wish to explore. |

|

|

Importantly, using the new approach allowed the practice room to become our research laboratory, where observations are recorded and analyzed to determine if we are on the right track and what the next experiment should be. This new method had only one problem: we knew of no one who had gone this path before. We were in many ways back to square one. We had to go back to the drawing board countless times designing new training approaches, new training armor, new safety gear, new training equipment, and new training weapons to get closer to the goal of our simulated combat tests. One definition of an expert is a person who has made all the mistakes that can be made in a very narrow field, and we were intent on making those mistakes. This concept of making mistakes and learning from them would become one of the guiding lights of Hurstwic. |

Our improvisational talents were put to test with this new method. We used anything and everything we thought might help us progress us as fighters, and more importantly, as researchers: heavy bags; focus pads; kicking shields; riot armor; dirt bike armor; padded sticks; nylon wasters; wooden wasters; blunt steel weapons; and sharp steel weapons. Yet, many of the tools we wanted just didn't exist. Destiny, however, sometimes has a plan. It was at this time that two new members joined Hurstwic.

|

Barbara Wechter is a make-anything-from-anything kind of a person. She could, for example, listen to our complaints of the limitations of a certain weapon when it came to testing or training and come back to the next training session with a purpose-built weapon that didn't have those limitations. Robin Cooper is a retired United States Army Special Forces member who brought to the table a clear and precise point of view on whether our combatives were on the right track or not based on his genuine experience. |

|

It was around this time that our creativity took off, creating new weapons to help us push the limits of our Viking combat research: marking weapons, that left a mark on one's training partner where the weapon hit; weapons that registered the hit on the weapon, so we could tell if the hit or the block was made with the edge or the flat; electrified weapons that gave a zap to one's sparring partner at the moment of the hit; soft weapons that were rigid enough to allow full-power attacks to unarmored sparring partners' more vulnerable bodyparts, but soft enough that there was little risk of injury; innovative composite axe heads that were stiff in some directions to allow for hooking and controlling moves, but compliant in others so there was little risk of injury in the hit; a set of blunt steel swords identical in mass and dimensions but with radically different "feels" due to changes in center of balance and moments of inertia to allow comparing swords having a high degree of controllability to brute chopping swords; weapons prepared so that, unbeknownst to the training partners; they would likely break part-way through the round; shields made out of a synthetic material that fractured under the hit of a synthetic blade waster in much the same way that a wooden shield broke under the hit of a sharp steel sword. |

|

Seven: Sharing the path

One of Hurstwic's goals has always been to advance the state of knowledge on Viking combat and share our newfound knowledge with others.

|

Our research was producing results that strongly suggested that Viking-age fights were not like anything we had seen published in books or on the web or in other modern sources. During his visits to New England, Reynir and I collaborated on a series of videos published on YouTube that show some of the fighting moves described in the sagas. Our goal was to illustrate some of the fighting moves that we believed were typical of the ways that Viking-age people fought and used their weapons. Using the information in Hurstwic's concordance of fighting moves from the sagas, and using our new approach to training, it did not take long to plan, rehearse, and shoot the videos, since the focus was on the moves and not on the choreography. These short clips were meant to introduce new ideas had an impact that we didn't foresee. Schools started using our clips to show students what fights looked like in the sagas they were reading, for this was the first time this material was available. We received requests from like-minded people who wanted to share our path. Yet at the same time, we rocked the boat. Other reenactors and researchers had a firm view of what Viking combat was, and they did not care for the path Hurstwic was now taking. |

We were pleased with the results and pleased with the reaction to these videos. We began to consider the possibility of releasing a series of training DVDs so that people distant from our home base in central New England could use our training methods. We decided to use the Hurstwic name to describe our method, our training, and our products such as the DVD. I had been using the name for the website for well over a decade, and it made sense to use an established name. Accordingly, we registered the Hurstwic name with the USPTO.

With the help of the participants in the Hurstwic training, we shot one DVD in 2011, and two more in 2012. The videos were shot with no budget, using video equipment that was on-hand, or borrowed, or stolen (temporarily).

It was shot in a limited time, and occasionally, guerilla-style on location. Perhaps the production values are not as high as a Hollywood feature film, but we firmly believe that what matters most is first-rate: the training taught on the DVD. |

|

|

Our research continues to grow and bloom, while the videos remain stuck in the time in which they were created. They remain useful training tools, but should be considered historic memory of where our research on Viking combat was at that time. |

We had received many requests to set up an affiliate program so other groups could use the Hurstwic name and method. This program was set up in 2011. We intentionally made the screening test difficult so that Hurstwic's previous record would not be tainted by inadequately qualified groups. Additionally, we were not seeking expansion. Instead, we were seeking fellow researchers who had the same intention as we in following truthfulness using science: groups that would add to the research, instead of skew it.

Eight: Next step

As we continued our path of research and discoveries, it became clear that to understand one aspect of the Viking lore requires one to understand them all. A good analogy is that of a hunter in pursuit of game, for example, reindeer. He must not only understand his rifle fully and how to use it, he must also understand all aspects related to the hunt: where to hit the reindeer; laws on reindeer hunting; where the reindeer graze; reindeers' sense of smell; from what direction to approach the reindeer so it won't catch the hunter's scent; and much more. Even though the hunter's only goal is to shoot reindeer as food for the family, he must understand the complete picture.

Similarly, a key aspect to our research is the use of layered sources. Focusing on a single source does not give the complete picture. We layer one type of source on top of another type of source on top of another type of source to build a strong structure and strong understanding. For example, we layer pictorial sources on top of archaeological sources on top of literary sources. The sources must all point in the same direction; if they don't, we have to stop and understand what is wrong. Is our underlying hypothesis wrong? Has the source been misinterpreted? Is the source an outlier? We don't focus on outliers or single examples. Instead, we seek the common thread that runs throughout all the sources. We seek to create a holistic picture of Viking combat.

|

We created special occasions so that we could experience, test, and study a range of Viking activities: hiking in Viking clothing; competing in stone lifting; horse riding; Viking ship rowing; and many others. |

The experimentation with these other Viking activities forced us to think of new ways to do scientific testing, using new measurement devices and data analysis tools. We brought these new measurement devices to the training room to take our combative testing to a new stage of data analysis and experimentation. |

|

Another aspect we also explored in detail at this point was outdoor training, taking advantage of winter weather and natural settings to better simulate combat situations from the Viking age. |

|

|

We also revisited our cutting training using sharp replica weapons. We had experimented with most of the targets traditional to swordsmanship: tatami mats; water bottles; melons; rolled newspapers; and others. Yet, we were not convinced that any of these were representative of a human body. Sharp cutting tests are a necessity to anyone researching Viking fighting or any other blade-based fighting. Without them, it's extremely difficult to understand what one is attempting to emulate in the simulated combat testing. For that reason, we went to the extreme of acquiring a pig that had been raised and slaughtered for the sole purpose of being our target in cutting tests. These cutting tests, though not flawless, clearly showed us some of the errors of our ways. In no uncertain terms, they showed the potency and efficacy of Viking weapons. This test would be ground breaking for our research. To our knowledge, no one had gone to these extremes with a cutting test before. |

Nine: Valhalla

These activities all took place at the time that Higgins Armory Museum was closing, and we were forced to look for a new research laboratory. It was a sad time, and it seemed that the road ahead was immensely rocky. Luckily, blessings sometimes come in disguise.

We had already broken the mold on how to do Viking combat research. We were following our own path of science, and our new laboratory would allow us to do tests ill-suited to a museum setting.

Our new laboratory was named Valhalla. Although it is a clichéd name for anyone familiar with Vikings, we chose it because it best represented the activities inside. In Norse mythology, Valhalla is a place where warriors fight, die, and come back to life only to repeat the same cycle the next day. At our Valhalla, we researched in a simulated combat setting and died countless simulated deaths only to repeat the cycle of research. Valhalla became a research center. It was here that our explorations and testing rose to a new level. Here, we could do time-consuming tests, rowdy tests, messy tests, and more scientific testing using more advanced scientific equipment. Throughout, we gathered more insightful data for our analyses. But more than a mere training hall, it became a research center and club house: a place where we could hold meetings, feasts, and non-physical educational programs for Hurstwic and for the general public. |

|

All systems, whether they be combat, religion, or politics, have their head: a front man and a poster boy, and that is what I had become. Yet, it is not the role that I sought. As a scientist, I wanted only the role of seeker of truth. It was of grave importance to me that Hurstwic not be a cult with Dr. William R. Short as its guru who has all the unquestionable answers. Hurstwic is and always has been a scientific community where researches don't wear a lab coat but instead, a mail shirt and bruises.

In our group, we don't have ranks, apart from instructor and not-instructor. There are no kings, no earls, no slaves. We are all equal in our contributions to our scientific endeavors.

|

For that reason, Hurstwic has done all that it can to free its researchers from the interpretations driven from the "experts" above. We strive to give the researchers direct contact with the sources we are testing so they can explore them themselves. For example, we teach the ancient language so our researchers can read the literary sources directly. We arrange with museums and collections for hands-on access to historical Viking-age weapons for the group to study. |

|

Ten: Walking in their footsteps

We sat down and pondered what our next big step in research should be, and it was clear. We had studied the weapons first-hand. We had studied how the weapons were used first-hand. What we had not studied first-hand was where the weapons were used: the historical battlegrounds of the Vikings.

Thus, our next logical step was to go to Iceland and shoot documentary films on saga heroes, photographed on the locations of some of the great battles of the Viking age, and in the literal footsteps of warriors of the sagas. Our next two productions were feature-length documentaries on the final battles of Gísli Súrsson and of Grettir Ásmundarson. We interviewed experts in related fields during the course of making our documentaries, making new friends and acquiring new special advisors. We tested out our ideas about the battles on the historical sites, walking in the footsteps of the saga heroes. This was an eye-opening experience, the next evolution in our research. We knew from here on out our research had to be deeper than ever before with an army of experts and specialists to guide us. Over the next few years, we honed our craft, our research, and our explorations at Valhalla. In most ways, it was smooth sailing. Our research methods became more and more precise, and tests we had done years before were put under more pressure. |

|

As our research went deeper and our research became broader, we were graced with more and more academics wanting to associate themselves with us. We were no longer perceived to be from the community of Viking hacks. Instead, we were now perceived as a research team having a clear goal and a proven track record who held answers that could be trusted: answers that they couldn't find elsewhere.

Hurstwic is not William R. Short nor is it Reynir A. Óskarson. It is not even the researchers that do the testing. Hurstwic is an eclectic team who fight together under the Hurstwic banner in search of knowledge, combined with countless experts who tell us in no uncertain terms if we are on-target or off-target in our research. These connections with academics and experts lead Hurstwic in many directions of explorations.

Eleven: The earth comes back greener

After more than six years of research, testing, training, and studying at Valhalla we made the decision to close Valhalla. It was a bitter day, but it was what was needed for the next step in the evolution of Hurstwic.

In our final training session at Valhalla, we opened the "time capsule" of Hurstwic training, pulling out all the old gear, and trying the drills and exercises and training equipment that we had used in our twenty-year history of training. It was eye-opening to see how far we had come.

Hurstwic has started over a few times in its history, as can be seen in this chapter, but in each and every case its renewal was built on the foundations of the older Hurstwic. That approach is exactly what we intend to do now as we move forward.

|

The Covid-19 shutdown gave us a good opportunity to gather the data from our twenty years of research and to analyze it in order to present a crystal-clear picture of what we know about Viking combat. That picture is presented in our new book, Men of Terror, and it is only the first step in gathering those data together. This is the building block from which we take our next steps, our next tests, and our next projects. And this is the milestone we have now reached in Hurstwic's twenty-year saga. Just like in the ancient sagas, we are merely slaves to our destiny. Hurstwic's destiny is searching for truth about how Vikings lived, died, and used their weapons. And so, the journey continues. Our unique approach to Viking combat research is based on: scientific testing; layered sources; and pressure testing our hypotheses. It has yielded some surprising results which are summarized in the book. This research has led us on many adventures. Some of the adventures include: |

Glíma is the name of both Viking-age wrestling and the national sport of Iceland. Hurstwic dug to immense depths in this little-revealed wrestling form, both in its origins and its evolution into the sport it is today. This research has resulted in Hurstwic being the only Viking combat research group accepted by Glímusamband Íslands, the official glíma association of Iceland and the torchbearer of this ancient wrestling system. |

|

Hurstwic works hand-in-hand with GSÍ to preserve and advance the art of glíma, such as submitting the application for glíma to be included in the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage (Icelandic text here, English translation here). We have given a presentation on glíma at Háskóli Íslands (University of Iceland). |

|

Hurstwic had a sit-down meeting with the President of Iceland to discuss our research findings. |

|

We have held meetings with renowned academics in several related fields to discuss our research results. |

|

We have been interviewed on national radio about our book and our research. |

|

We have met with archaeologists at their field excavations to discuss the interpretation of the artifacts they have uncovered. |

|

We have given a presentation at Ţjóđminjasafn Íslands, the National Museum of Iceland, interpreting the artifacts on display in the light of the research in our book. |

|

We have lectured at Háskólinn í Reykjavík (University of Reykjavík) to physics students on the physics and science behind our research on Viking weapons. |

|

We have lectured to Icelandic language students at Háskólasetur Vestfjarđa (University Centre of the Westfjords) on how our research into the ancient language of the Vikings informs us about Viking combat and about how the echoes of that combative society linger in the modern Icelandic language. |

|

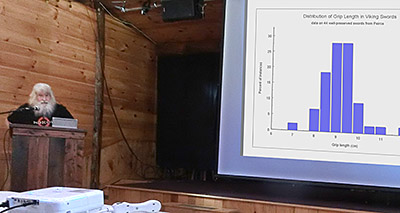

We gave a lecture on our research into Viking-age swords and their use at the Ashokan Sword Seminar of the New England Bladesmith Guild. This presentation has ignited at least one collaborative research project to better understand the capabilities and limits of Viking-age swords. |

|

We have presented at the Worcester Art Museum as part of their Master Series lecture program, to introduce museum guests to a newly acquired historical Viking sword for the Higgins Armory collection at WAM. |

|

Part of the Hurstwic group had deep interest in the art of iron smelting, and in the puzzle of how iron was made in saga-age Iceland. With the assistance of smelters, archaeologists, geologists, and other specialists, we figured out the puzzle, and in a public festival, we made the first iron in perhaps 700 years in Iceland using all Icelandic materials. That iron, and those research results, were the basis of a special exhibit at Ţjóđminjasafn Íslands (the National Museum of Iceland) that ran through 2024, and were discussed in a lecture we presented at the museum (now available on YouTube) on our use of experimental archaeology in our research. |

|

Hurstwic has recently embarked on a research project to gain new understanding of Viking weapons and their use by combining motion capture data of weapons being wielded with computer models of historial Viking weapons. |

|

|

In 2024, Hurstwic conducted as series of experiments to examine the commonly-used Viking battle tactic of attacking a man by burning his house. The experiments concluded with a public Fire Festival at Eiríksstađir in Iceland where we built a number of Viking-age house structures, instrumented them, and burned them down. The data we collected, and the video recorded show us that the tactic was more brutal, terrifying, and horrific than depicted in the literary sources. The experiments were conducted in cooperation with the National Museum of Iceland, the Fire Department of Dalir, the Fire Protection Engineering Department of WPI, the Icelandic Forestry Service, and others. Numerous videos of the event can be found on the Fire Festival page, along with this preliminary report video. |

Even after more than twenty-five years of dedicated research, there is still much to discover, to learn, and to explore. We continue to use our three-legged approach, but now the legs are: scientific testing; fundamental kinesiology; and use of a wide-range of overlapping sources, with no other limits. It is our hope that these chapters in Hurstwic's saga will not only be new information shared with the larger community of academics, independent researchers, and scholars, but also that they will also be a valuable tool to assist in furthering the knowledge about Viking combat so that you, the reader, will assist us with the next chapters in the Hurstwic's saga of research and learning. |

|