|

|

Norse Mythology

In Gylfaginning, Snorri Sturluson enumerates the twelve gods and the thirteen goddesses who, together with Óðin and his wife Frigg, make up the Norse pantheon. Stories survive for some of the gods, preserved in the Poetic Edda, the Prose Edda, and other Icelandic manuscripts.

But no stories have survived for many of the gods and for most of the goddesses. We know that many more stories once existed, because quotes from those stories are mentioned in other literature from the period.

The articles linked below provide a brief introduction to some of the Norse gods and goddesses, as well as a summary of a few of the stories. I strongly encourage interested readers to avoid my dull summaries. Instead, read the originals, or read R. I. Page's witty and pithy summaries, or Crossley-Holland's retellings of the myths. These books are readily available and are listed in the references section of this document.

|

|

|

That these myths were preserved at all is a surprise. The Icelanders who committed these stories to vellum manuscripts were, without exception [pix], Christians. Why would Christians preserve stories about heathen gods, who were thought to be the personification of Satan? At least a part of the answer is that without an intimate knowledge of these stories, it would not be possible to create or to understand skaldic poetry, thought to be one of the greatest forms of art, not only in the Viking age, but in the centuries that followed. |

|

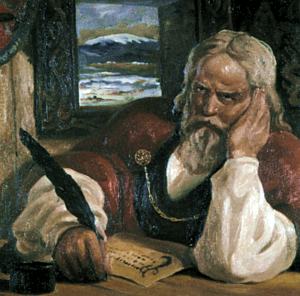

Early in the 13th century, the Icelandic poet and chieftain Snorri Sturluson (right) wrote a book, commonly called the Snorra Edda, to teach young poets the art of skaldic poetry. Part of that teaching included a summary of the mythological stories on which the poetry depended. |

|

|

Other surviving sources of mythology include eddic poetry preserved in the Poetic Edda, as well as Viking-age picture stones (left). None of these sources are complete. The picture stones illustrate only a single episode in what are often complex stories. The eddic poetry, while thought in many cases thought to be well-preserved Viking-age verse, is incomplete and abstruse. Snorri is thought to have added to and modified the stories, euhemerizing them to make them more acceptable to his Christian audience. But taken together, the sources reveal a set of stories that maintained at least some level of consistency as they were told and shared among the northern people over a period of many centuries, from well before the Viking age until well after. |

The stories tell of gods and goddesses that were far from being perfect or immortal. They battled and wooed and wedded. They were, by turns, strong and weak, petty and noble, brilliant and dense. The stories range from the hauntingly powerful verses of Völuspį, to the comedic and irreverent verses of Žrymskviša. We hear of a golden age, free of strife, which was lost, resulting in a downward spiral of bickering and feuding and killing. This was the world in which Viking-age heathens lived: a world threatened by monsters barely held in check by the gods.

|

|

©1999-2026 William R. Short |

The illustrations accompanying these stories were taken from a wide variety of sources. Some of them are stone carvings from the Norse era. Some are drawings used to illuminate medieval Icelandic manuscripts. Most were created during the Romantic era at the turn of the last century when there was a resurgence of interest across Europe in the Norse mythology. Works by Winge, Hardy, Dollman, and others are represented. Some of the sketches are modern illustrations.

We believe these images to be in the public domain, except where indicated. We ask that any copyright holders who feel their intellectual property is being used improperly to contact us so that we can either make proper arrangements to use the material, or so that we can remove the material in question.